Blog

Occasionally, I like to write to complement my photography (primarily for myself but also with the outdoor community in mind). If I’m fortunate enough, and I’ve put the effort in, my thoughts make their way into print.

Visiting Scotland - From Chile or Argentina

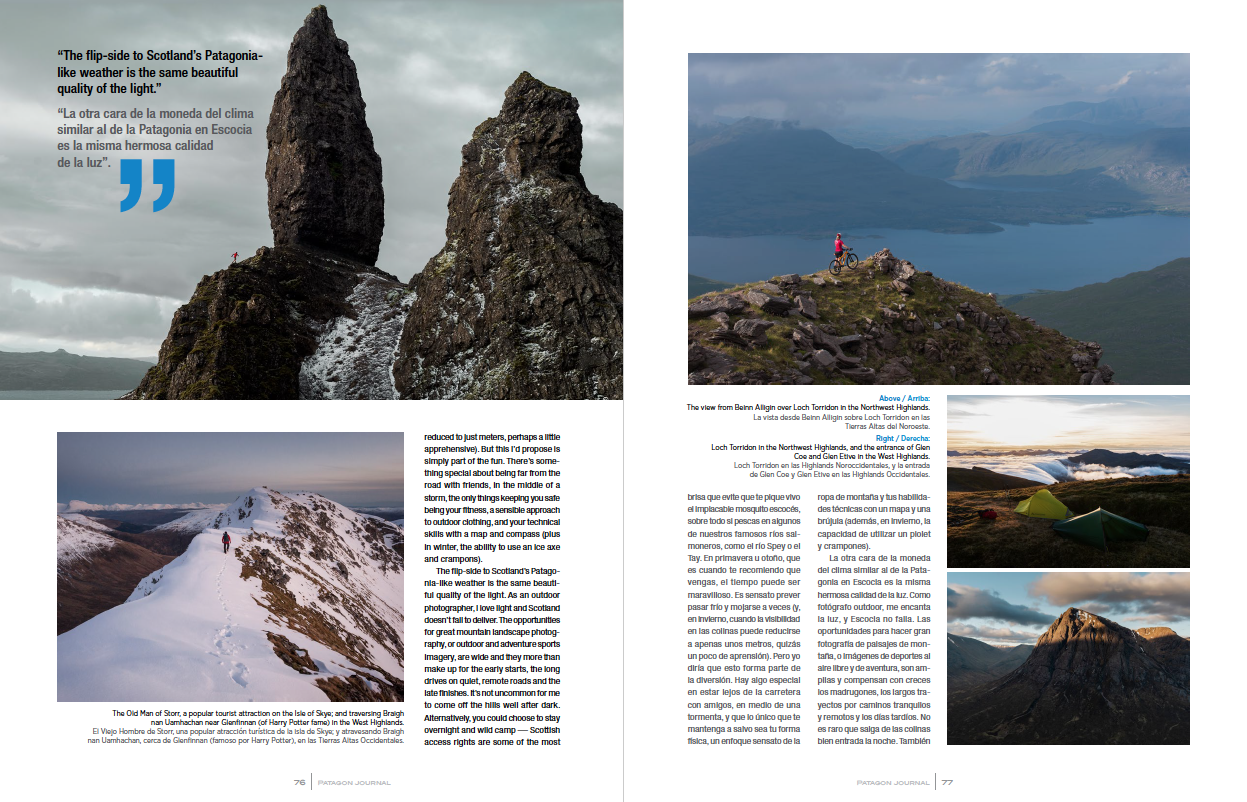

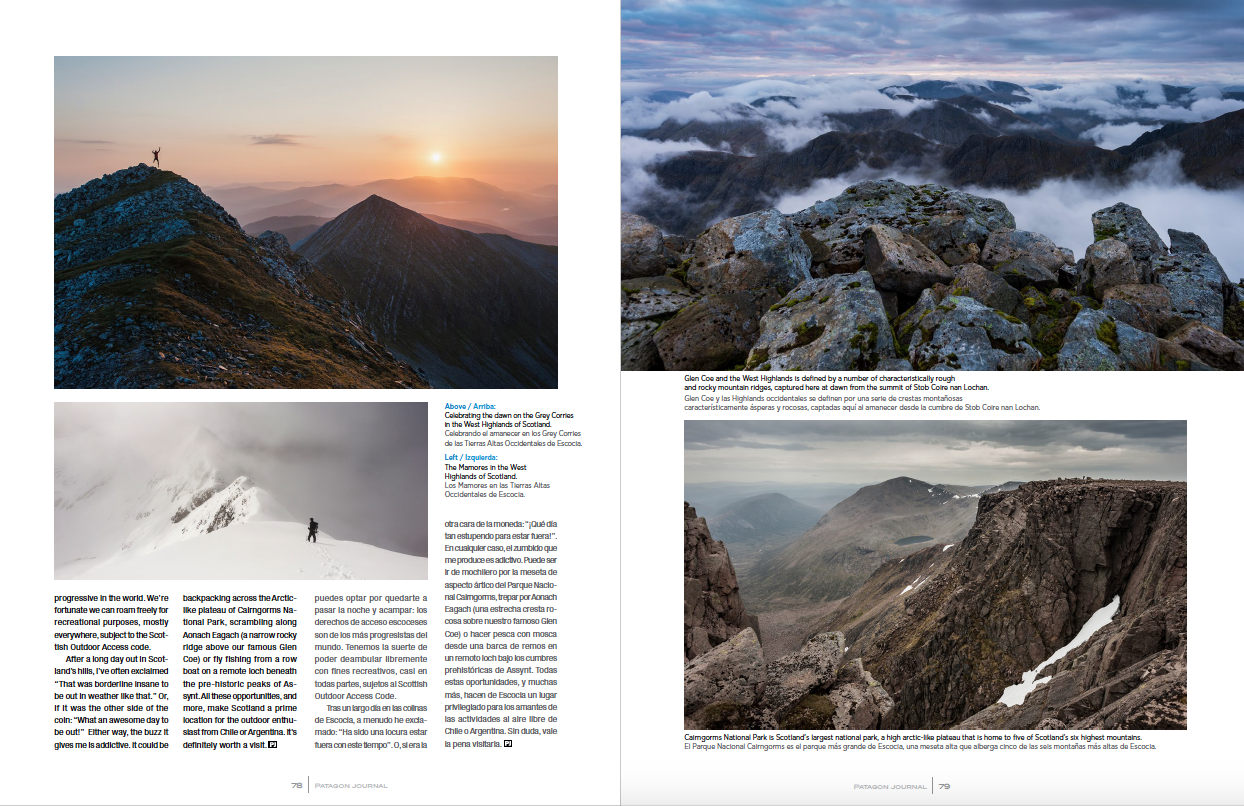

Reasons for why people in Chile or Argentina may choose to visit Scotland for outdoor adventure instead of heading south to Patagonia and enjoying their own compelling landscape.

Written for and published by Patagon Journal - Patagonia's magazine for nature, the environment, culture, travel and outdoors. To support the launch of a new Destinations feature called ‘My Country’, I chose to focus on the rationale for why people in Chile or Argentina would choose to visit Scotland instead of heading south to Patagonia and enjoying their own compelling landscape.

(See also my Q&A with Patagon Journal)

Morning view from the summit of Ben Lui, a Munro in the West Highlands of Scotland

The rationale for visiting Scotland for an outdoor adventure is perhaps similar to the choices you’d make for travelling to Patagonia. Northern giants of Chile and Argentina aside, when viewed on a global scale, neither of our country’s mountains are the highest (Scotland’s tallest hill, Ben Nevis, is just 1,345m/4,413ft) but they pack a punch, offering the outdoor enthusiast a multitude of opportunities for a world-class mountain adventure — in Scotland’s case, without the skills or a guide needed for a venture onto Patagonia’s glaciers.

Running, hiking and mountain biking in the Scottish Highlands is my passion. Towards the end of each year, I’ll start to relish a Winter’s season walking and mountaineering. People often find this strange, because I’m not talking about the deeply cold, snowy ‘postcard’ Winter views you may get in the arctic countries, such as Sweden or Finland, but the bone-chilling, ‘just-above-freezing and the sleet’s blowing sideways’ maritime climate that myself and many other Scottish hillwalkers rejoice in (and which Patagonia aficionados will know all very well).

Scotland’s weather has a reputation for being wet, and sometimes harsh. Regular visitors to Patagonia will be used to that. In high Summer, the weather’s often warmer than expected but you’ll appreciate a breeze to prevent you being bitten alive by the relentless Scottish midge (especially if you’re fishing on some of our famous salmon rivers, such as the River Spey or Tay). In Spring or Autumn, when I’d recommend you visit, the weather can be awesome. It’s sensible to plan to be cold and wet at times (and, in Winter, when visibility on the hills can be reduced to just metres, perhaps a little apprehensive). But this I’d propose is simply part of the fun. There’s something special about being far from the road with friends, in the middle of a storm, the only things keeping you safe being your fitness, a sensible approach to outdoor clothing and your technical skills with a map and compass (plus in Winter, the ability to use an ice axe and crampons).

The flip-side to Scotland’s Patagonia-like weather is the same beautiful quality of the light. As an outdoor photographer, I love light and Scotland doesn’t fail to deliver. The opportunities for great mountain landscape photography, or outdoor and adventure sports imagery, are wide and they more than make up for the early starts, the long drives on quiet, remote roads and the late finishes. (It’s not uncommon for me to come off the hills well after dark). Alternatively, you could choose to stay overnight and wild camp — Scottish access rights are some of the most progressive in the world. We’re fortunate we can roam freely for recreational purposes, mostly everywhere, subject to the Scottish Outdoor Access code.

After a long day out in Scotland’s hills, I’ve often exclaimed “That was borderline insane to be out in weather like that”. Or, if it was the other side of the coin, “What an awesome day to be out!”. Either way, the buzz it gives me is addictive. It could be backpacking across the Arctic-like plateau of Cairngorms National Park, scrambling along Aonach Eagach (a narrow rocky ridge above our famous Glen Coe) or fly-fishing from a rowing boat on a remote loch beneath the pre-historic peaks of Assynt. All these opportunities, and more, make Scotland a prime location for the outdoor enthusiast from Chile or Argentina. It’s definitely worth a visit.

Runner’s World - ‘Rave Run’

Words and images published as ‘Rave Run’, a regular double-page spread which opens the popular Runner’s World magazine.

Various words and images published to illustrate ‘Rave Run’, a regular double-page spread which opens the popular Runner’s World magazine.

Rave Run - Cairngorms National Park

Rachael Campbell high above Loch A’an in Cairngorms National Park, Scotland

The location

Cairngorms National Park is home to five of the six highest mountains in Scotland. A network of paths join together summits and offer the trail runner plenty of opportunities for off-road, mountain fun. It’s not always essential to keep to paths. The Avon slabs (pictured) are nestled deep within the park. Alongside Shelterstone Crag, they oversee remote Loch A’an, a large freshwater loch 725m above sea level.

When to visit

Spring is a great season to visit. Remnants of snow will necessitate caution (and the right equipment) but, otherwise, often pleasant weather and the lack of the Scottish midge (Scotland’s famous but wretched biting insects) provides runners with positive returns.

Rave Run - Grey Corries

The experience

Charlie Lees on Stob Coire Chlaurigh in the West Highlands of Scotland

An ascent of Stob Choire Claurigh in the West Highlands of Scotland, at first on steep grass and then on broken quartzite, rewards runners with spectacular views. This vista, looking north-east at sunrise over the subsidiary top of Stob Coire na Ceannain, demonstrates the value of an early start.

The location

Stob Choire Claurigh is one of four Munros (Scottish mountains over 3,000ft) that make up the Grey Corries, a long, scalloped ridgeline that snakes its way south-west towards Ben Nevis, the UK’s highest peak.

A challenge

The Grey Corries form part of Ramsay’s Round, a challenge set by Charlie Ramsay in 1978 to run 24 Munros in 24 hours. A shorter version of Ramsay's round, which also includes the Grey Corries, is called Tranter’s Round. It is named after Philip Tranter, son of the novelist Nigel Tranter.

Rave Run - Liathach

The location

Liathach is one of big three mountain ranges in Glen Torridon (along with Beinn Eighe and Beinn Alligin) in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. Those with a head for heights will relish the challenge of the exposed scrambling across the top of the Am Fasarinen pinnacles to reach the Munro summit but an alternative route, that is much more runnable, is to find a high traversing path, which presents you with spectacular views across the glen.

The challenge

Munros are Scottish peaks over 3,000ft (914.4m) high. Numbering 282 in total, they offer adventurous trail runners a myriad of opportunities for mountain fun. Paths up steep sides provide access to ground such as the broad, Arctic-like plateau of the Cairngorms in the east to the narrow grassy ridges and rock that is more prevalent in the west. Conditions change quickly and it's wise to be prepared. Spare warm clothes and a map and compass for navigation, plus the knowledge to know how and when to use them, is essential.

Rave Run - Tarmachan Ridge

Joanne Thom on Meall nan Tarmachan in Scotland

The location

The Tarmachan ridge is a prominent viewpoint as you drive the A85 road towards the West Highlands of Scotland. Starting from the summit of Meall nan Tarmachan, a Scottish Munro 1044m high, the ridge winds its way south-west for 3.5km, over the shapely peak of Meall Garbh and beyond, offering great views north over Glen Lyon as you go. Take advantage of a car park at 450m, which takes some of the sting out of the initial ascent, or be a purist and start at the roadside 250m further down.

The challenge

Meall nan Tarmachan is within the boundary of Ben Lawers National Nature Reserve, which the National Trust for Scotland manages for conservation and public access. Home to seven Munros (Scottish mountains over 3,000ft/914.4m high), the reserve offers trail and mountain runners a variety of challenges, from a few hours to all day (or even overnight).

Rave Run - Black Cuillin, Isle of Skye

Donnie Campbell running on the Old Man of Storr in the Isle of Skye, Scotland

The location

Scotland’s Munro Round record holder, Donnie Campbell, approaches the rocky outcrop known as the ‘Old Man of Storr’ on the Isle of Skye in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. The 160-foot high pinnacle is part of the Trotternish Ridge, whose stunning, raw landscape has featured in several films, including The Wicker Man and Prometheus.

The run

You can run or walk up and down the Storr on a 2.3-mile trail. The foot of the Old Man is steep and a bit of a scramble, but once on the rocks surrounding the base, your reward is magnificent: panoramic views of the Sound of Raasay and the Scottish mainland beyond.

Creating great outdoor sports photographs — Six things to think about

Hints and tips on what to think about if you're interested in improving your outdoor sports photography.

A paraglider in front of a glaciated Aiguille du Dru (Les Drus) near Chamonix in France

What makes a compelling outdoor sports photograph?

Why someone proclaims a photograph to be a ‘great photograph’ is usually a personal thing but when I see an image that really captures my attention, it’s usually because two or more things have taken place;

People — A dynamic moment has been captured, usually in a creative way.

Place — The photographer has used an inspiring location that really connects me with the scene and helps me understand what’s going on (either a location I’ve not seen before or, if I have, they’ve photographed it in a unique way).

Lighting — They’ve made great use of natural or artificial light to bring the image to life.

With the above in mind, here’s 6 tips you can apply when taking outdoor or adventure sports images, to help you catch people’s attention.

1.) Set yourself up for success

Anthony Meyer preparing his trekking poles for balance on a snowy, windy and wild Winter’s day out walking in the Scottish Highlands

A tedious opener, to be sure, but this is the only tip that’s related to the type of camera you have (e.g. a DSLR, mirrorless or compact camera which enables you to change camera settings). If you’re using a mobile phone, feel free to skip ahead.

a.) Prioritise a high shutter speed — I’d always recommend opening your camera manual and understanding how things work, if you don’t already. This will enable you to move out of Auto mode and optimise your chances of creating great outdoor or adventure sports images.

Shutter speed priority is a good choice initially, along with an understanding of ISO, so you can maintain the high shutter speeds required to freeze action. You can use slower shutter speeds, e.g. to express movement or when experimenting with panning techniques but if you don’t keep your shutter speed up, you’ll most likely have lots of shots of out-of-focus athletes.

Common shutter speeds for outdoor sports are;

1/2000s to 1/500s — Athletes moving quickly (e.g. running, swimming, mountain biking, etc.)

1/500s to 1/250s — Athletes walking (e.g. hiking, backpacking)

1/60s to 1/15s — Panning shots

b.) Shoot in burst mode — Professional outdoor sports photographers take a lot of shots. I’ll commonly shoot 1,000+ frames in a shoot where the athlete is moving quickly (and more if need be). A primary reason I do this is I’m looking to capture the athlete in the most dynamic pose for that sport. Whether it’s hiking, running, cycling or swimming, there will be certain body postures or movements a talented or elite athlete will repeat which look entirely natural and which epitomise the sport. (In trail or mountain running, for example, there are perhaps two moments in a stride that look hero worthy — the rest I often simply delete straight away). Shooting in burst mode maximises the chances you’ll capture those two moments.

c.) Use continuous auto-focus — Set your camera to continually auto-focus as you depress the shutter. Take lots of shots but don’t just ‘spray and pray’. Give your camera a chance and part depress the shutter long enough for it to to secure focus on the athlete before you actually shoot. Then take your burst of shots, giving yourself the best opportunity to capture the moment you’re looking for.

2.) Shoot sports you know

David Hetherington ascending the Scorrie on Driesh, a Munro in Cairngorms National Park, Scotland

Outdoor and adventure sports such as running, hiking and cycling all have pivotal moments that help define the sport (e.g. a whitewater kayaker powering through a foamy wave with one paddle in the air and the other immersed in the roiling water). If you shoot sports that you know, you’ll appreciate when these occasions are going to arise and it’s easier to anticipate the action. If you don’t know the sport, you can study videos or pictures of it online, or simply watch someone before you take photographs (contact your local sports club or team and see if you can make friends with who they view as the elite members). Establish the type of pictures you like, and why, practicing initially to emulate those shots before you advance and progress to your own style.

3.) Choose great locations

Donnie Campbell running at Désert de Platé near Chamonix, with Mont Blanc in the background

The internet is such a valuable resource these days for a landscape photographer and there’s many useful tools that will aid your planning (such as Google Maps, Google Images, Fatmap and the Sunseeker mobile app or Photographer’s Ephemeris). You can research in detail exactly which locations should be worth going to and when, with the huge advantage of knowing in advance where the light will fall. A great deal of work can be done at home or in the office and if you’ve planned correctly, it’s hopefully simply a case of waiting for a spell of good weather.

Once I’m on location, I’ll almost always start by thinking about the landscape first and then framing my images based on what I see in front of me. If I want the landscape to be a key element in a shot, say on a trekking or a mountain biking shoot, I’ll look for things that help bring depth to a scene (e.g. something in the front, middle and back of the image) and I like to have a strong horizon, such as a rocky mountain ridge, that helps me to offset an athlete in the frame. On a surfing shoot, where the landscape may be less of a priority, I’ll look instead to where the waves will break in a frame, so I can position the surfer accordingly. Whereas on a shoot with lots of graceful movement, say for a yoga or capoeira shoot, where I’d prefer to focus on the detail, I’ll choose to ignore the landscape altogether and focus completely on the athlete.

4.) Prioritise good light

Mountain biking on the Grey Corries in the West Highlands of Scotland

Very simply, get up early and stay out late. Then get up early again the next day. Maximise the time you’re out shooting when the light is good. Don’t discount days when it’s really cloudy, as the sun can break through and shine magical light onto your scene in seconds. Consider adding your own light if the weather, or your vision, warrants it (for example, using a reflector or an off-camera flash to call attention to a certain part of the image, such as an athlete’s face or clothing).

Technology-wise, mobile apps such as Sunseeker are indispensable. They show the trajectory of the sun through the day, and more. When you’re researching a location, or you’re on location, think about where the sun currently is and where it’s headed. At dawn and dusk, an obvious position to place yourself would be facing east or west. Consider though positioning yourself at right angles to the sun or even shooting right into it, and see what drama it adds.

5.) Try different angles

Alexis Basso trekking across the rocky boulder field en route to Col de la Portette and Refuge de Platé near Passy Plaine-Joux, France

There’s no specific position I’ll put myself in when taking a shot. I do though like being above a person so I will often look out rocky outcrops that I can climb upon and take in more of the scene. If there’s nothing suitable, I’m not averse to bringing a step ladder with me, if the location accommodates it. Or standing on the roof of a vehicle. One tip I’d share would be to try and get yourself into a position that someone taking a snapshot of the scene wouldn’t think of. Get up high or lie on the ground. Do both. And then try something else (such as using an element in the landscape as a foreground). Move around — consider a full 360 degrees — and seek to maximise the shot potential in every scene.

6.) Focus on composition

Gore-sponsored endurance athlete Naomi Freireich mountain biking on Beinn Alligin, a Munro in the North-West Highlands of Scotland

Once I’m happy with how I’ve framed the backdrop, I’ll consider how best to position a person or persons within it. When composing an image, I like simple backdrops, with no distractions around the athlete and really clean edges to the frame (which I think is super important — distracting elements at the borders of your image can take your viewer’s attention away from the key element, i.e. the athlete). To help you picture where I add people into my shots, think of an imaginary grid. My aim usually is to position folk on the horizontal and vertical intersections, either entering or exiting the frame. But I’m not averse to placing athletes right into the middle of a scene, if I feel it looks good.

Key takeaway?

Practice and master the above until it becomes second nature so you can free yourself up to focus on your creativity, seeking out moments which can help you to stand out from the rest

Appreciate that, other than exposure, there’s no real right or wrong. Try different things and see what happens. Take lots of shots and share them widely. Gather feedback and keep learning (and, above all, enjoy the process).

A Peale’s dolphin leads Team East Wind as they sea kayak on the Strait of Magellan in Chile, Patagonia, during the Patagonian Expedition Race

Licensing outdoor photography for commercial and editorial use

Advice on selling / licensing outdoor adventure images to commercial and editorial clients.

Supporting Mountain Equipment to advertise their Starlight sleeping bag range

I’m currently negotiating a price for the commercial use of a series of outdoor sports images I’ve captured, which a UK company wishes to use for advertising purposes on a new website they’re designing. The difficulties I’m finding these days as a photographer is securing what I feel is a fair price for my images in an industry that, by and large (in a world of micro-stock, good-quality cameras, apps such as Instagram and a world that likes to share) is perilously close to the bottom in regards to the price of stock photography. I thought therefore I’d share the process I go through when a client asks me to provide them with a price for an image and what steps I take to secure what I feel is a fair price for the intended use.

Why do I care about intended use? In the photography business, photographers license the use of images to clients rather than sell images outright so they retain the rights to the image for future use. The car rental business is a common analogy, where, if you place yourself in role as the client, you’re hiring a car for a specific use for a specific period of time and the price you pay is appropriate to your usage. To add some complexity to the car analogy, there’s also the value of the photograph to you and how valuable it is to the client, plus how unique your image is (e.g. can your client easily get similar images elsewhere?). As a photographer, it’s important to understand these things and be diligent to ensure the payment you receive for your photographs is an accurate reflection of the usage you provide. There’s many considerations when it comes to licensing images and it’s really not so simple when you factor in there’s no agreed list of prices online that you can refer to for specific usage (such as those communicated online by a car hire firm). I often wish photographers were more open about the prices they receive (or charge) so we can do more as photographers to ensure as an industry that we’re being rewarded appropriately for what is, by and large, a very expensive occupation to have.

1.) Pricing images for editorial use

The first thing I’ll do when I receive a request for use of an image by a client is to check the purpose. Is the usage going to be editorial reasons (such as a magazine) or for commercial use (e.g. for advertising purposes)?

If a client wishes to use my photography for editorial purposes, my next step is always to ask what they plan to do with the image (e.g. illustrate a cover, fill a double-page spread. use it in a table of contents, etc.). More often than not, the Editor or Art Director will also share the price that they’re willing to pay for that use (the common field of play in the markets I operate being the magazine sets the rates for editorial use rather than the photographer). In 2019, I find there’s little point negotiating this price unless my image is very unique but I’m not afraid to walk away if I think the value is too low (nor do I shy away from requesting additional fees if there is a creative writing to be delivered on top of the photography, e.g. above and beyond a standard caption). My main thought process is, am I happy with the price that’s being offered (see the accepting reduced rates section below) and what usage license will I offer in return.

When is editorial use not editorial use?

Editorial use I class as use by a magazine, newspaper or trade publication that’s purely for consumers’ information only, either for knowledge or entertainment. Editorial use by a company where the goal of the editorial piece is to help them sell products (e.g. on a blog) I something I’d class as commercial use.

(This is not always black and white. On one occasion, I had a puzzle. An editorial magazine wanted to use my image but the page they would use it on was being used to selling products for companies who had paid for advertising space. Is that commercial or editorial use? I decided it was editorial as I had no corporate client to bill the work to. It’s often a tricky job pricing stock photography).

Don’t be afraid to query rates. A returning client offered me a specific amount for a double-page spread

2.) Pricing images for commercial use

The two types of commercial use licenses commonly offered by photographers are Royalty Free and Rights Managed. Both types of licenses have pros and cons and, depending on my client, one license may be more suitable for them than the other.

Royalty Free — A Royalty Free license is a license clients can purchase which provides them with the permission to use an image in perpetuity, in any fashion they choose, print or digital. In other words, I’m giving a copy of that image to my client along with a license that says they own that copy from then on (important — just the copy, not the copyright) and they can use the image how they wish without having to pay me any more money in the future. Royalty Free is a common license I’ll be asked to provide by clients working for smaller or medium-sized companies as most of these companies don’t set aside the bigger budgets (or have a need) to pay for the exclusive use that is often offered under a Rights Managed license (see below). The advantage to me as a photographer in terms of Royalty Free licenses is that these are generally licensed for non-exclusive use and I can continue to license the image to other clients for the duration of any existing contracts (plus the transactions are fairly quick as there’s no complex negotiation required).

Rights Managed — Images offered on a Rights Managed basis enable photographers to retain more control about how their images are used by a client, plus they give us the ability to re-license images once an initial contract has ended if our clients wish continued use outside the terms that have been agreed. I’ll grant a license for a specific use of a photograph, which I’ve agreed during negotiations with the client, giving them full permission to do what they want with the image but only within the parameters of that specific use. They only pay for what they need, which suggests the value I derive from those images is completely linked to the client’s use. Or is it?

3.) What price to charge for an image license?

The answer? Only you will know. If a client shares how they’re going to use your image but asks you what your price is, they’re putting you slightly more in the driving seat. On such occasions, the internet is your friend. Stock photography websites such as Getty Images share their prices online and you can establish what they charge their clients for editorial use. (I have in the past compared a few different stock agencies and calculated an average price but I’d caution against this as their prices can vary dramatically). I prefer to choose a single stock agency that I’m happy to use as a benchmark and revisit it regularly to see how their prices are changing. I also research rate cards to see if I can find out what magazines and newspapers are charging clients to purchase advertising space in their magazines and conduct lots of research before I provide clients with a quote (including asking other photographers what they charge and whether they feel the price I am proposing is undercutting the market). My primary goal is to arm myself with enough knowledge so I can make sensible decisions as to how to run my business (and please my clients) but in a way that doesn’t harm me or other photographers.

The general approach I take to agree a price is to;

Decide how unique my image is

Define how much it means to me

How much it means to my client

What the client’s budget is

Intended use?

Duration of use?

Exclusive or non-exclusive use?

Consider any price being offered against research I’ve conducted

Decide if the rate is appropriate for me

Decide my own price

Negotiate if appropriate

Share the image plus the usage license (including terms and conditions)

Finalise and close

Why would you choose to accept a reduced rate?

Sometimes, a magazine or corporate client will offer you a rate that is not comparable with the value you’ve placed on your image. You can negotiate, walk away or, alternatively, decide to accept that rate if you feel you’re going to gain in a different way. Chase Jarvis, an American photographer and creative entrepreneur has some good advice that I regularly refer to, about only accepting work when two out of three criteria have been satisfied. It’s based on commissioned work but the principles I think are good to keep in mind and can be easily adjusted for stock photography, by changing them to what’s important to you. It’s guidance I value and which helps me makes me feel that I’m making my business decisions for the right reasons.

Licensing images at reduced rates can harm yourself plus other photographers by making it easier for the market to drive the price down. It’s tempting to take what money you can get (accepting that clients have limited budgets) but your photography has a value (and if clients are approaching you, they value it too). My recommendation would be you establish a price that reflects the value of your photography and don’t accept reduced rates without negotiating as hard (but politely) as possible to ensure you’re getting something from the contract that is of sufficient value to you.

4.) Protecting yourself with image licensing contracts

It’s important to manage the risks of licensing your photography for commercial and editorial purposes. (I’ve written an article on business risk management for photographers). For each and every usage license I provide a client, I protect both myself and my client by ensuring my invoice contains clear instructions on the terms of the license (including the duration of use and any restrictions) plus a copy of my terms and conditions, which outlines, amongst other things, that I retain the copyright and what risks the client is running if they use the image in a non-agreed way.

If you’re looking for a template for your photography terms and conditions, Lisa Pritchard’s excellent book ‘Setting up a Photography Business’ contains the wording I originally used for my terms and conditions, which I modified to suit my needs after consulting with a lawyer. In regards to stock photography, I’ve established what risks I am open to in regards to clients using my images in a way I’m not aware of (or have not licensed) and I make sure to protect myself (with my client in mind) as far as possible.

More reading

Jim Pickerell — Negotiating Stock Photo Prices (Out of date and generally out of stock but packed full of useful information and you may find copies being sold second-hand online)

Richard Weisgrau — The Photographer’s Guide to Negotiating (Amazon link, non-affiliate)

Lisa Pritchard — Setting up a Successful Photography Business (Amazon link, non-affiliate)

What’s the worst that can happen? Business risk management ideas for photographers

A selection of risks an outdoor photographer is open to, along with some thoughts on how to avoid or mitigate them.

Important — This isn’t legal advice. It’s a sharing of knowledge as to how I approach the management of certain risks in my outdoor photography business. My list of risks is not exhaustive. Consult a lawyer please if you need an expert view.

Competitors capsize in rough waters during the Oban Sea Kayaking Race, an annual 20km race around the island of Kerrera off the west coast of Scotland. The pair were back in their boat fairly quickly, obviously confident that their skills and experience (at what I’d call ‘self-arrest’ in mountaineering terms) were sufficient for them to be confident they could manage any risks they’d experience during the race, e.g. falling overboard.

A number of photographers I’ve spoken with over the years have surprised me by sharing that they didn’t have an overly considered approach as to how they manage risk within their photography business. Yes, they had mature workflow and backup processes in place to protect their images and signed contracts as to what they were committing to produce but in the context of mitigating risk across their whole business, I was often left feeling they were leaving themselves open to problems should something go wrong. To support myself in that regard, and the community, I’ve illustrated what risks I feel a photographer is open to and shared some ideas as to how we could mitigate them.

Whose photo shoot is it anyway?

A key thing I like to agree early on in a contractual discussion is clarity as to whose shoot it is. For example, am I working for the client and they’re recruiting me along with other resource, such as models? Or is the client contracting out the production of the whole shoot to me and therefore I’m assuming all the accountabilities? Will I be sub-contracting elements of the work to other third parties to help me complete the job (e.g. a film-maker or a digital technician)? Answers I can secure to these and other related questions helps me to understand which risks are applicable for that commission and whether they sit with me or with my client or a crew. It’s important for me to understand the potential risks in a shoot and the controls I have in place to mitigate the ones which are relevant to me. Highlighting what’s left protects me but also helps me to support my clients.

What risks does a photographer need to consider?

A solid approach to risk management is a key attribute for a photographer. It’s not as creative or as fun as taking photographs and it won’t stop things going wrong (a key skill in photography is problem solving) but the goal I’d suggest is to plan ahead and limit your liabilities as far as possible. You’ll soon realise you won’t be able to mitigate every risk but can I propose your goal, as far as possible, is to be aware of the risks you’re carrying in your photography business and be comfortable with your approach to these before you perform any work. Consult a lawyer for professional advice.

1.) Working for yourself

Here is a selection of risks I’d suggest you’re open to as a photographer once you have been commissioned for a photography shoot;

Risk you have to do more work than expected — Is the scope of the work you’re being contracted to do fully documented and signed off by all parties? Consider what you’re being asked to do and ensure you’re happy you’ve adequately budgeted for it in terms of cost and time in your photography estimate. Are there additional images being requested on set? Extra processing required after submission? Be clear up front if this is above and beyond the cost of any estimate you’ve provided and the contract you’ve agreed.

Risk you hurt yourself (and can’t complete the work) — Especially so in the world of outdoor and adventure sports photography, when you could be photographing people running, hiking, trekking in remote places, mountain biking down rough ground or surfing and kayaking in turbulent waters, there’s a higher chance than usual of you hurting yourself whilst on a job (e.g. breaking an ankle or wrist) and not being able to work. Personal accident insurance could cover you in such an eventuality. Be up front with the insurance company about your activities and ensure you are covered accordingly.

Risk you break equipment (and can’t complete the work) — Outdoor photography is especially hard on camera gear. Rain, sand, dust, salt water, rocks, etc. can all have a catastrophic effect on your equipment and stop your shoot short. Equipment insurance will help but ‘real-world’ insurance is better — ensure you have a backup for each piece of equipment you need on a shoot (including peripheral items such as cables). Being able to switch to working equipment quickly and confidently in a crisis is a professional approach and will make you look competent in front of your client.

Risk you do poor work — Not something many people want to admit, but we’re all human and mistakes can (and likely will) happen over the course of your career. Knowing the capabilities of your equipment, being able to use it inside out and avoiding the need to try anything you’ve not practiced repeatedly prior to a shoot is the best advice I would offer photographers against the potential for work that’s not quite as good as it could or should be. Private indemnity insurance can offer you peace of mind that any issues you experience won’t be catastrophic financially (although your reputation, i.e. your brand, will almost certainly take a hit).

Risk you hurt others — Public liability insurance can cover you for costs that are brought upon you in a court of law related to claims made by members of the public related to your business activities. Think of someone walking past your shoot location who trips over your camera bag and hurts themselves.

Risk you’re seen as liable for the crew’s actions — You’ve been hired by a client to create photographs. A budget has been allocated to the shoot for a Production Manager to manage the shoot and keep it running on time. Included is funds for an assistant plus a person who will carry strobes and other equipment to the photography location. You’ve recommended the services for a Safety Officer, a professional mountain guide you know who can help identify and manage risk across the photo shoot overall. Plus there’s two or three models needed for the images and a stylist responsible for hair, make-up and wardrobe. That’s a crew of people who are all working together to help you create photographs for the client. The key question to ask yourself in such situations is who is hiring who and, if it’s you, how do you protect yourself from any potential issues?

In the example above, the only crew I’m responsible are those I’ve brought to the shoot myself, i.e. the assistant and the load carrier (but only in certain ways — see the ‘Working with a crew’ section below). The Production Manager, Safety Officer, models and stylist are all contracted by the client (as am I). In such cases, I’d want my documentation to make it clear for the client that I appreciate they are an integral part of the shoot, and I do have quality expectations of them, but I have no obligations as to how they act, nor the effectiveness of their work.

Risk you’re seen as liable for the client’s actions — As above, but with a different example. What if your client or a member of their staff hurts a member of the public on a shoot? Or injures a member of your crew and they are unable to work? Is it clear who will be liable and therefore whose insurance needs to be claimed off? You may wish to propose to the client that they put in place shoot-wide insurance that covers everyone involved in the production of the photographs. If they say no, make sure there are no expectations at all that your insurance covers anyone other than you on the shoot (unless you’ve clearly agreed up front that you’re taking on a full production role, which I’d always recommend includes shoot-wide insurance).

Risk you lose work — You may well have an efficient backup system in your office which packages your content nicely onto appropriate RAID so it’s stored in multiple locations both on and offline. But what happens on set? How big an issue would it be for you if your memory card stopped working, for whatever reason, and you lost all the images from the shoot before it had finished? It’s unlikely given the quality of today’s ‘big brand’ memory cards (I use SanDisk and Lexar) but you might wish to consider backing up your images in camera to two separate memory cards or tether or transfer them wirelessly to a laptop whilst shooting. Another method would be to quote the client up front for the recruitment of an aforementioned Digital Technician, who can be responsible for backing up your images regularly whilst you shoot (plus working on images your client has picked during the shoot and processing them for approval).

Note — If your client accepts there is a risk here but doesn’t wish to pay to mitigate it, you could choose to record this in your documentation for the shoot (e.g. an email summarising decisions and actions or a RAID document you’ve produced which details risks, assumptions, issues and dependencies).

Risk your client doesn’t accept your work — Make it clear in your terms and conditions what classes as a finished product (i.e. what good looks like according to the brief). Ideally, you don’t want to be guessing if your client will like your work when you send it across. Enabling them to review images and sign them off as being compliant with the brief in the field will remove that pressure. Being tethered to a computer whilst you work will also aid that process. (If the client won’t be at the shoot, a common solution is to include a clause in your terms and conditions highlighting that you have the final say as to what constitutes an ‘on-brief’ image) .

Risk you can’t use or re-use your work — The copyright in your photographs should remain with yourself as the photographer (otherwise you won’t be able to use of your work outside the boundaries of which it was shot and, depending what is in the contract, perhaps not at all). Include a clause in your terms and conditions that details that you, as the photographer, own the copyright to all your work and you retain the right to use the images for the purpose of self promotion at any time and for all purposes outside the terms of any licensing period you are providing for the client. (The only proviso may be if you’ve been asked to embargo images for any period of time).

2.) Working with a crew

This section applies when you’ve agreed with the client that you’re responsible for hiring people to help you carry out the logistics of the shoot. This could include models, load carrying or more technical tasks such as production management, camera and lighting or a digital technician. I’d strongly recommend, if you are responsible for contracting with someone directly, mapping out the specifics of that relationship with that person and ensuring you have a detailed contract in place which outlines the nature of the contract, what good looks like for them and you use that to limit your liabilities.

Risk they consider you liable for any loss of income — In the outdoor and adventure photography world, this is especially relevant when you’re hiring, for example, professional athletes as models and there is a risk that they hurt themselves and are not able to earn their income. Position yourself in such a way that any resource you contract work to is aware there are risks and they’re accepting that they are competent enough to independently identify and mitigate those risks and are fully responsible for accepting any consequences of their actions. If it is not clear to you what the risks are (your crew will be the experts in their own field so seek their advice), schedule a session with each one and potentially a Safety Officer to discuss the shoot beforehand and agree any boundaries you’re not willing to cross. (This doesn’t stop you from always being vigilant on set. If you’re not comfortable photographing someone performing a task, or you see someone acting in a manner that could be dangerous to themselves or others, be confident to say so).

Risk they don’t perform — For various reasons, the standard of work you receive from a member of any crew you recruit may be less than which you expected. Choosing your resource wisely will mitigate this (e.g. you‘ve worked with the person before or taken recommendations from trusted friends) but it’s only fair to be clear to your crew what you expect. Document this for each person and ask that they agree to it up front.

Risk they hurt themselves — Imagine you’re on a photo shoot and you’ve hired an assistant to help you carry gear to the location. For an outdoor adventure photography shoot, this could be to a crag where you’re photographing climbers or you’ve hiked to the top of a mountain to take images of runner at dawn. You’re confident in your own abilities to manage the risks in such a situation but how do you get peace of mind that your assistant is competent and won’t put themselves or others at risk (and, potentially, consider you liable for any loss of income should they get hurt on what they see as your photo shoot). Ensure they’re aware that your insurance only covers you and your recommendation is they have their own business insurance in place. (You may only choose to work with people who have appropriate insurance in place).

Risk they hurt others — As above, recommend to each member of your crew that they have their own Public Liability Insurance. (Also consider whether you wish to contract with anyone who doesn’t).

Risk work is lost — If you hire a competent digital technician they will bring quality processes to the shoot as well as their expertise, which should include regular backups to minimise the risk of images being lost. Asking for assurance of this makes entirely good business sense, as does outlining what you expect from a digital technician and what good looks like. Document this in a contract you agree with them before the shoot.

Risk models don’t sign model release — In the example I gave above, it’s the client who has hired models but the model release I’d suggest is of most value to you as it dictates how your images can be used (and how you can use them in the future). Make it a key task in the shoot to ensure that you or someone on your behalf is responsible for securing a signed model release.

Risk they damage equipment and the shoot can’t be completed (or they consider you liable) — If you’re hiring crew for the photography shoot, check what equipment is included in the crew rate and seek assurance, like you, that they’re bringing back-up equipment in case of equipment failure. Flag up front that, if a member of your crew’s equipment becomes damaged during the shoot, they need to be sure that it’s covered on their insurance, or a shoot-wide insurance policy.

3.) Working with a client

The following risks apply either to commercial work or where you’re selling something direct to a consumer (e.g. a print or a workshop).

Risk they expect more than you’re expecting to provide — I’d recommend you clearly outline what you’re providing as part of your service or product offering but, more importantly, what you’re not. This will help identify potential gaps in people’s understanding.

Risk they hurt themselves on set and they think you’re liable — As mentioned above, be clear on what you are responsible for and what not

Risk they don’t like your work — Again, covered above by you including a clause in your contract that the client signs off work in the field (or, if they’re not attending the shoot, they’re accepting that you as the photographer have the right to decide what good looks like).

Risk they pay you too long after the shoot (and you’re out of pocket) — Request an up-front payment of the full production expenses in your estimate when you have to do work ahead of the shoot. (Include any expenses for your crew).

Risk they don’t pay you at all — It’s unusual but cover yourself by including clear terms in your contract that outline the implications of any non-payment of work that is delivered on brief. Consider requesting a deposit up front, e.g. 20% of your shoot fee and your crew’s fee on top of the full production expenses.

Risk they use your images where or when they’re not supposed to — Make sure any model release and your usage license clearly outlines the boundaries of where the images can be used. Be specific about any exclusions and expiry date. If your client has recruited the model directly then you should not be open to any risk because the contract is between the client and the model (but you do have a vested interest in the content of the release if you want to use the images going forward). If it’s you who has contracted with the model and agreed the model release, and the client uses the images outside the terms of that release, the model may be entitled to claim additional funds for any breach of contract. Be sure that it’s not you that will be liable for those costs.

Summary

Nearly all my thoughts above are based around my being able to identify who is responsible for what in a photo shoot and ensuring that any risks I may be inadvertently exposed to as a business are mitigated as fully as possible. I’d summarise this as follows;

Consider all the risks you may be open to as a business

Put processes in place to mitigate those risks

Put controls in place to assure yourself that your processes are working

Check those controls on a regular basis

Use contracts to protect yourself, as far as possible

Don’t blindly accept other companies’ contracts. Take control of your business and protect yourself.

More information

I started my photography business using the advice provided by Lisa Pritchard in her excellent book, ‘Setting up a Successful Photography Business’. Included in the appendix is a series of templates Lisa recommends for business contracts (including an excellent one for terms and conditions). For that reason alone, and more, I’d say this is an essential purchase for any photographer.

Attempting Tranter’s Round, a 24-hour mountain running challenge in Scotland

Route information, logistics and photographs for runners interested in the Philip Tranter Round or Charlie Ramsay Round, two long-distance routes across the mountains above Glen Nevis in the West Highlands of Scotland.

A resource with an account, photos and logistical information for people interested in Tranter’s Round, a 24-hour mountain running challenge to complete 18 Munros (Scottish mountains over 3,000ft high) above Glen Nevis in the West Highlands of Scotland. It includes the story of two failed attempts I’ve made so far along with a successful round, but which wasn’t within 24 hours.

Devil’s Ridge on Sgurr a’Mhaim in the Mamores

“Compared with all the huge routes and records that have been taken on and achieved by many people [during the Coronavirus lockdown], Tranter’s Round is quite modest. But it was a big deal for me and the perfect test of my new found running legs”

I can’t recall the first time I was aware of Tranter’s Round, nor when I became interested in accepting its challenge (which is to visit the summit of 18 Munro mountains in Scotland in a 24-hour period). It was likely around the time I first photographed sponsored mountain runners such as Salomon athlete Donnie Campbell and Arc’teryx’s Tessa Strain, or outdoor guide Paul Tattersall, all mountain athletes who make travelling quickly over rough ground seem relatively effortless. During those times, I received a sense of the pleasure that comes with moving in the hills without lots of equipment and I took inspiration from that, increasing my fitness until I was able to travel quicker over rougher terrain myself, for longer periods of time. The key attraction for me being I can join together otherwise unconnected hill-walking routes and spend more time outdoors.

Already a keen hill-walker, I wasn’t being entirely unrealistic with my ambition, which in this case was to finish Tranter’s Round in under 24 hours (or, if not, to complete the trip in a single push). I have a decent base level of fitness from many hours spinning each week and my body is used to the rigours of ascending and descending hills, having hillwalked and backpacked Scotland’s Munros and Corbetts for many of my 53 years, often for 12+ hours per day. I do have experience of moving for much longer periods of time, such as 24 hours of alternate laps at the Strathpuffer and two consecutive 21 hour days in the Cairngorms Loop, but those efforts were on a mountain bike. Tranter’s Round is a mountain running challenge where, in a 24-hour period, you visit the summits of 18 Munros (Scottish peaks over 3,000ft high) in the Lochaber region of Scotland. I’m not however a runner. But I know my pace and, as long as I kept moving, and sustained forward motion, I felt I *should* be able to complete it in around 23h 30mins. If my feet didn’t play up — more on that later — and the fairy dust aligned.

What is Tranter’s Round?

Named after the son of the late Scottish author, Nigel Tranter, Tranter’s Round is a 24-hour mountain running challenge set for hill runners by Philip Tranter in 1964 when he connected (at the time) 19 Munros in the West Highlands of Scotland (the Mamores, Grey Corries, Aonach Mor and Aonach Beag, Carn Mor Dearg and Ben Nevis) in a 36-mile epic that covered 20,600ft of ascent. Today, Philip’s round ticks off 18 Munros (the Scottish Mountaineering Club demoted Sgurr an Iubhair in the Mamores after a re-measuring of the peak in 1997) but it still forms a challenging route over an aesthetic horseshoe of ridges and peaks that starts and finishes in Glen Nevis. From the Youth Hostel near Fort William, the route heads out of the glen onto the first Munro of the round, Mullach nan Coirean. From there, you head over Stob Ban, with two out and backs along narrow ridges to Sgurr a’Mhaim and An Gearanach, before completing all ten of the Munros in the Mamores on the 1010m high Sgurr Eilde Mor. A long grassy descent, a crossing of the Aibhainn Rath and a steep pull up to Stob Ban leads on to the Grey Corries, where you turn and head for home, with a great view in front of you as you traverse a fantastic series of ridges that culminates in the great bulk of Aonach Beag and Aonach Mor. A good choice of route is key to attaining their summits, over 4,000ft in altitude, where a steep descent and ascent to Carn Mor Dearg and an excellent traverse over its narrow, rocky arete leads you to Tranter’s Round’s final summit, Ben Nevis, the UK’s highest peak. ‘All’ that’s left is the 4,500ft descent to reach your starting point and the completion of your round.

Tranter’s Round is not an organised event. There’s no sign up or checkpoints, nor navigational aids. Neither is it a race but there is a fastest known time, of 8 hours 27 minutes 53 seconds by Fort William-based GP, Finlay Wild. This may give the impression that completing it in 24 hours is easy, more so when you understand that the route has been superseded in fell-running terms by Ramsay’s Round, named after Charlie Ramsay who lengthened the route to 24 Munros, 56 miles and 28,500ft of ascent in 1978. (The record for Ramsay’s Round is also held by Finlay Wild, who completed it in 2020 in 14hrs, 42mins, 42secs, beating the previous record of 16hrs, 12mins, 32secs which had been set in 2019 by his friend, Es Tressider). My desire to do a shorter route in 24 hours is nothing special (to anyone other than me). I’d read about people routinely doing it in under 20 hours. I have respect for anyone that can do it that quickly but when I extrapolated my times from shorter routes, I realised that they’re operating many, many (my wife recommends we should add a third many) leagues above me. It was clear that I’d be performing at my limit to finish with just 30 minutes spare. I had little margin for error or slowing down due to fatigue and it was much more likely that I’d fail to do it in 24 hours. (I did always, deep-down, have some confidence that I would finish it in one push or else I might have just as well gone camping).

An initial taste

In 2014, three friends and I set out on a two-day backpack of Tranter’s Round. At the time, I hadn’t any thoughts of attempting the route in one go. It wasn’t an entirely pure approach, as we ascended Mullach nan Coirean the night before to bivvy on its summit, and I missed out An Gearanach to dry out a wet sleeping bag. We also didn’t finish as we bailed off Aonach Mor in an unexpectedly cold blast of June rain, complete with hailstones, that chilled us to the bone. It did however allow me to appreciate the length of the route. Looking back, it also provided me with some good data to work from (16 hours from Mullach nan Coirean’s summit to the Aibhainn Rath), which is well behind a 24-hour time but this hadn’t been our intention.

During 2015 and 2016, I had casually pondered the 24-hour challenge, going so far as to make notes and do some detailed planning. Eventually, in January 2017, I committed and began to prepare myself for the rigours of 20,000ft ascent and descent in a single day. I started by teaching myself how to run, jogging from lamp-post to lamp-post along a cycle path as I walked the dog at night (the classic ‘couch to 5km’ approach). Benefitting from the additional fitness, I took to the Pentland Hills, a collection of grassy peaks c.500m high overlooking Edinburgh which hadn’t attracted me as a hillwalker but provided the stimulus for me to put in extra effort, as I interspersed fast walks uphill with jogging along the tops and running back towards town, initially on my own but later with a friend, Chris Hill. I really enjoyed these excursions but, throughout, I was increasingly afflicted by an acute discomfort in the soles of my feet.

My earliest recollection of foot pain when hiking was in 2011, towards the end of a 4-day backpack in the Knoydart peninsulas, when I experienced an intense burning pain in the ball of my feet. Since that trip, I’d often had pain on hill-walking trips but I did nothing about it other than blame my boots. A painful memory is on the aforementioned backpack of Tranter’s Round where, at the end of our first day, the balls of my feet were so tender, I recall crying out when I put weight on them as we crossed the waters of the Aibhainn Rath barefoot to spend the night at Meanach bothy. The crux however was when I was photographing Donnie Campbell on a Ramsay’s Round attempt in December 2016. Donnie was successful (setting a new record time for Ramsay’s Round in the winter season) but the pain I experienced as I descended Ben Nevis was, frankly, awful. In 2017, after multiple visits to a podiatrist, I was referred to a surgeon who diagnosed Metatarsalgia in both feet plus multiple Morton’s Neuromas, an affliction that I learned is commonly found in females who wear too-tight high-heel shoes. (At the time, I was on my sixth pair of La Sportiva approach shoes, which have a narrow toe box and perhaps this, plus repeatedly strapping my feet tightly into cycle pedal straps, pre-cleats, whilst spinning multiple times a week, could have been a contributing factor).

My foot pain manifests itself in two very specific ways. Metatarsalgia starts with a thickness in the ball of my foot, like I’m standing upon a CR2032 battery that’s embedded under the skin. This radiates a nerve-like pain that eventually travels across the soft parts of my feet that ramps up, remarkably so when I clench my toes (at one point I thought the pain was from a large blister deep under the callused skin but I have it when there’s no blister as well). It’s always highly painful at the time - like I’m walking on deeply swollen feet - and, at it’s worst, I’m left feeling for days afterwards like someone has been beating the soles of my feet with a club. Separate to this is Morton’s Neuroma, which starts off with the sensation of a broken almond shell or a pea embedded within the sole of my foot, behind my outer two toes. The nerve eventually gets aggravated and the pain grows, manifesting itself in a manner similar I’d propose to someone biting my toes or periodically squeezing them with a pair of pliers. Both I’d estimate it as around four or five on the comparative pain scale (if you applied that to hill-walking) and a six on my descent from Ben Nevis. Which I appreciate could be extremely worse but it always fosters unpleasant thoughts, especially when I am many miles away and thousands of feet above my starting point.

Postponed - First for injury, then due to Coronavirus

From a podiatry perspective, my understanding is there’s four approaches to foot pain. Stop what causes the problem and rest. Orthotics or cortisone steroids and, if that fails, an option for surgery. I didn’t see the benefits of rest (the issue came back repeatedly in 2017, despite many breaks) and orthotics didn’t make any difference. Steroid injections thankfully fixed one foot but not the other and eventually the surgeon’s advice was to operate and he explained a procedure where he would saw through bones in my right foot using a minimally invasive procedure and reset the bones so they were lifted off the neuromas and I wouldn’t experience as much pain. Which sounded extreme but it was an approach the surgeon explained had a high rate of effectiveness and, very keen to be pain-free, I accepted his recommendation. Thankfully, in general, the operation, in March 2018, was a success and almost exactly twelve months later, after a few months delay with what I was initially afraid was a Lisfranc injury (when I returned too soon and damaged my foot descending Bidean nam Bian in Glen Coe), I was back jogging in the Pentlands with no torment other than that caused by a lack of fitness.

By Autumn 2019, my foot felt strong again, as did my legs. Buoyed by a 16-hour day ticking off nine Munros on the north side of Glen Shiel, I was confident I could cope with the rigours of Tranter’s Round. During our trips to the Pentland Hills, my friend Chris had indicated he’d like to join me and we had made plans to continue our training over the Winter and schedule an attempt for May 2020. (Summer 2019 was out as I don’t have much desire to be exerting myself on the hills when it’s warm — plus, eurgh, midges — and I was away that Autumn). I also really don’t operate well in the heat and my preference was to do it on a nice Spring day when there is cool temperatures and a full moon. The additional darkness didn’t concern me as nearly all my training in the Pentlands had been done at night, aided by a great head-torch, Petzl’s Nao+).

Chris and I’s plans for numerous joint training sessions in 2019/20 were unfortunately scuppered when it was Chris this time who needed a break for surgery, the result of a meniscal tear to his knee during the previous year’s Glen Coe marathon. I spent the Winter plodding around the Pentlands, sometimes with friends and often on my own, following an 18km route twice a week with 800m ascent. These excursions I topped up with lots of spinning plus jogging on the streets (totally not enjoyable) and some day trips hiking on Scotland’s Munros (very enjoyable, a memorable day earlier in the year being the completion in a day of all five Glen Etive Munros, which involved 32km and 8,500ft ascent). Unfortunately, as the training progressed, I started to again experience foot pain. My right foot (the one I’d had surgery on) had been fine all year wearing trainers but in bigger boots, on bigger hills, it began to flare up, especially in the ball of my foot and I was again experiencing lots of discomfort. Trying not to be too negative (but often failing), I planned another visit to the surgeon, who indicated over email that a further steroid injection might help.

2020 you’ll likely recall was the year of Coronavirus. My visit to the hospital for a steroid injection was cancelled, as was any hill exercise at all. Eventually though, I was able to get back out on the hills and if there was any positives from the Government-enforced lock-down (achingly, during the most extended period of glorious weather I’ve seen for years), it was a reinforced desire to take opportunities whilst I can. 2021 will be my 50th birthday and, although I’m fitter than I’ve ever been, running (which for me means mostly downhill) has to be somewhat destructive on my joints and I’d like to protect them so I can keep hillwalking into an old age. Tranter’s Round however was an itch I felt I really had to scratch (along with two others I have, which is to attempt the Highland 550 Trail and to cycle the West Highland Way in one go). My goal during Coronavirus therefore was to maintain my fitness as much as possible. Chris and I made a commitment that we’d make an attempt on Philip Tranter’s route as soon as lockdown was over and we were back to hill fitness.

Finally some proper preparation

Whilst researching the internet for tips on preparing for the Bob Graham Round (Charlie Ramsay’s Round’s English equivalent and the 24-hour round in the UK with the most amount of information online — Paddy Buckley’s round makes up the trio for Wales), I’d read that my focus should be on height rather than distance in training, aiming for 10,000ft per week. Long days hillwalking is perhaps the ideal preparation for something like Tranter’s Round, multiple hours on your feet I’m confident being key, and I added a few Munros to my tally (reaching the 200 mark), along with some new Corbetts. The Pentland Hills however were Chris and I’s main training ground and we repeatedly traversed a route from Flotterstone to the drove road west of West Kip, out and back, twice and sometimes three times a week, traversing twelve summits over a 15km distance with 1200m (3,900ft) ascent, which we interspersed occasionally with a trot around the Pentlands Skyline race route (an entertaining 16-mile, 6,200ft route which we definitely should have taken more advantage of).

An initial plan we had to do the route in September 2020 was postponed when a unseasonable weather forecast indicated cold rain, strong winds and below freezing temperatures due to the windchill. I appreciated the weather would never be perfect but we did want to stack the odds in our favour so we changed our approach and instead of booking ahead (we’d planned to stay in the Glen Nevis campsite) we agreed we would just keep an eye on the weather and if we had two good days forecast in October, we’d go at short notice. I’ve found this to be a much more effective approach for visiting Scotland’s hills, having spent many days over the years out in terrible weather for no real reason other than “we said we were going out”. The downside on this occasion though was the additional darkness, which in October lasts from 6.30pm until 7.00am following morning. It was all a moot point however when COVID restrictions once again kicked in and we were left contemplating when we could make an attempt in 2021.

-

In June 2021, we finally stopped talking about Tranter’s Round and headed north to Fort William. The weather was almost perfect with cool temperatures forecast (seven degrees Celsius at 900m during the day and five degrees Celsius overnight) with light cloud cover and a gentle breeze. Aesthetically, I’d wanted to attempt the route clockwise but we weren’t too keen about traversing An Garbhanach in the Mamores in the dark so we headed in the traditional direction and climbed Mullach na Coirean first. The first hill of the day for me is always the hardest as my body temperature takes time to settle as I transition from being fairly sedentary to hoofing up a hill. As usual, I began my ascent sweating hard and I had to put much greater of an effort into things than I expected, as I attempted to keep up with Chris, plus a quartet of lads in their twenties who, even though they were carrying big backpacks with sleeping gear, raced off very easily up the hill. A positive was it meant we reached our first summit in 2h30mins, one hour ahead of plan (we had based our timings on Naismith’s calculations) but it was clear that, despite having rested for a week, I wasn’t comfortable with the quick pace up the first hill (which in my defence is 900m ascent) and I was conscious that my pack was overly heavy.

Despite the six years thought I’d put into it, the majority of my time in the final weeks and days running up to our Tranter’s Round attempt I’d spent planning and re-planning. Much more than I care to admit. Frequently, I’d add items of clothing, equipment and food to a checklist I’d prepared and then remove them, and then I’d repeat the exercise until I felt I was happy. I’d then repeat that exercise over the following days. I’ve always been of the mind that you should carry enough clothing and equipment to last the night, if required, as well as an appropriate first-aid kit plus plenty of food but all additional weight slows you down and, with speed being key, and no support on our attempt, the challenge for me was to take as little as possible whilst remaining comfortable I’d stay safe. I run very hot so I wear the minimum amount of clothing whilst I’m moving, which means taking enough protective gear so I’d be warm for the worst conditions when stationary (but not taking so much it that I’d be overly comfortable and it slowed us down). I eventually ended up with what I felt was an appropriate balance (but which turned out to be entirely inappropriate), which gave me a total weight of 7kg, including food and water. This is somewhat light for hillwalking but still fairly heavy if you are trying to move quickly. (I recall reading somewhere the big difference that each extra kilogram added to someone else’s ascent times).

We touched the cairn at the summit of Mullach nan Coirean as soon as we arrived and left straightaway for the second peak, Stob Ban. I was looking forward to getting into a rhythm as I cooled down and started to enjoy myself but unfortunately it never materialised - the day proved much hotter than forecast and I spent the majority of the day feeling nauseous (foolishly, I didn’t put on any sunscreen - in my recollection there was minimum bare sun - and I ended up with first degree burns on my arms and neck, both of which are still a deep red colour one week later). This queasy feeling impacted on my desire to take on food and water - and likely affected Chris’ mental well-being as I walked behind him burping all day - and I only consumed 2400 calories of the 9000 calories I carried with me.

Despite never setting out to do so, I appear to be able to keep moving and not bonk despite not taking in lots of solid food. I was confident therefore in my ability to keep moving somewhat efficiently over the hills, even if there was no running. The two Munros at either end of the Ring of Steall, Sgurr a’Mhaim and An Gearanach were fun (if farther apart than I recollected), the loose descent from Am Bodach interesting (Stob Coire a’Chairn not so much) and, after an enjoyable scramble, we were back at the bealach beneath An Garbhanach at 5.00pm, after summiting An Gearanach still one hour ahead of our 24-hour schedule. A stop here for water however, plus conversations with others, ate into our programme and by the time we’d ticked off the somewhat interminable ascent of Na Gruagaichean, traversed the fine ridge to Binnein Mor and negotiated the steep descent to Binnein Beag (where we had another lengthy stop), we were at the summit of Sgurr Eilde Mor at 11.30pm, now 30 minutes behind schedule, but with ten of the eighteen Munros in the bag.

Chris had displayed strength all day and I had perked up after our breaks, and in the cool of the evening, the ascents of Binnein Beag and Sgurr Eilde Mor were hugely enjoyable. The hills of Lochaber at dusk in Summer are a fine place to be and our descent from the summit of Sgurr Eilde Mor to the Aibhainn Rath, on soft grass, was a joy, at least to begin with (there was nothing wrong with it, it just seemed to go on for ages, and the temperature appeared to increase again after we’d donned our head torches on the way down). The waters of the Aibhainn Rath, although low, mandated wet feet but once crossed we stood confidently at the foot of Meall a’Bhuirich, facing the 600m ascent to the Munro, Stob Ban, the first of the Grey Corries, but not nearly the highest.

I’ve ascended the steep slopes of Meall a’Bhuirich before, back in 2014 when we scaled its eastern flanks from Meanach bothy and again in 2012 up its western flanks in Coire Rath on a winter backpack. I’ve also descended from the summit of Meall a’Bhuirich to Meanach bothy one year when the weather put a friend and I off a traverse of the Grey Corries. Because of the effort involved, I wouldn’t say it’s my favourite hill and my ascent with Chris reinforced that opinion as we followed Finlay Wild’s .gpx track directly up its abrupt southern flank and crossed the bealach in the dark to reach the summit of Stob Ban.

It was 3.00am and we were now 60 minutes behind a 24-hour finish. I wasn’t overly concerned, my minimum benchmark for success being we complete the route in a single push, but I was getting tired. Feeling hot and queasy all day had been a grind and, outwardly, I groaned as I recalled the effort in our ascent to Stob Ban, as I knew we needed the same to get us to to the summit of Stob Choire Claurigh. My hopes were pinned however on this peak perking me up as there was a lot of light - we were close to the Summer solstice - and the summit’s got such an amazing view, with the rocky Grey Corries ridge snaking away aesthetically into the distance and the Aonachs and Ben Nevis on the horizon. We’d also be heading home and I was confident this would offer some psychological benefit for my wearying mind.

Our pressing need was to get some water. There’s a lochan at the bealach beneath Stob Ban, which I know from past experience is usually stagnant and filled with tadpoles but there’s a stream on the Coire Rath side and we planned to use this to keep us hydrated along the ridge. My mind had already wandered to the idea of stopping again for a short break (for no real reason, other than to put off the next 380m ascent) when Chris, without notice, abruptly announced he was done. A pain in his knee, not new as it had caused some curtailing of activity whilst we were training in the Pentlands, had been causing him some discomfort during the last few hours and had quickly ramped up to a level that was intolerable. I’d no idea - stoically, he’d not said - but the descent from the summit of Stob Ban, basically a big pile of loose scree, had exacerbated it very quickly to a level where he could only hop down the hill in great discomfort. A quick conversation ensued and we agreed to descend to the bealach and decide what to do next.

It’s not hard to stop an outing when a friend is in pain (especially when you’re also really tired) and when we weighed up our options it suggested going higher up would simply make it more difficult to come back down. We promptly called it a day and, despite my announcement that it would be a “one and I’m done”, agreed a few days later that we’d return and try again.

-

A common phrase when you fail at an endurance challenge appears to be that ‘the wheels came off the bus’. In my case I’d suggest it’s the opposite. In terms of achieving Tranter’s Round, my legs (i.e. the wheels) appear to be fine but the bus itself (my body) doesn’t appear to be able to keep up. Round two therefore unfortunately ended after an almost identical ascent/distance as our first attempt, entirely on my request this time, after a repeat of the sickness feeling all day (which I’ve narrowed down to drinking my calories instead of eating them, and therefore piling litres of slightly salty water onto an empty stomach), plus general fatigue from the intense sunshine and an injured foot (not neuroma-related but macerated skin I didn’t treat early enough which tore and turned into a full wound).

We chose for our second attempt to go clockwise, starting with an ascent of Ben Nevis. The forecast was 24 degrees Celsius in Fort William, decreasing to 21 degrees around the summits. After an eight-hour day in the Pentlands the previous week in similar heat I was confident I could deal with it, as long as I had enough water, and I added in an extra water bladder so I had the capacity to carry 2.5 litres between water points. My pack weight was therefore heavier (c.8kg including water) and I still anticipated very little running.

After long denigrating the ‘pony track’ on Ben Nevis, preferring the view of the north face that’s offered on other routes up the mountain, I found I really enjoyed it and it made for an efficient ascent of the peak in 2.5 hours, an hour under our schedule. The morning however was super hot, with no wind. A single patch of snow higher up was a godsend and I packed the snow under my hat and tried to keep cool as we ascended to the summit. Despite being midweek, the top of Ben Nevis was super busy but after we left the summit and descended towards Carn Mor Dearg, the numbers dwindled, to just a few on the fun, blocky arête. By the time we descended the east ridge of Carn Mor Dearg to the bealach above Coire Guibhsachan we were entirely on our own.

Our ascent to Aonach Mor from the bealach was a steep grind in the heat and our slow going, along with our choice to scramble along the Carn Mor Dearg arête, rather than take the bypass path, cost us time. There’s much easier ground out and back to Aonach Mor summit and on to Aonach Beag and we did try running for a while but it didn’t last long. Aonach Beag summit however and the descent to Stob Coire Bhealaich (aka Stob Coire a’ Chul Choire) lifted both of our spirits. It was simply glorious. The views were excellent and the feeling of adventure was still high.

There are three common routes between Aonach Beag and the Grey Corries. I had done two of them in ascent, heading west, one of which is termed in the mountain running world as ‘Spinks Ridge’, after Nicky Spinks, a Cumbrian farmer who’s completed a double Ramsay Round, and the other was the original Charlie Ramsay line, which involves a very steep exit/entrance on bare scree into a gully topped by a large rock overhang. A quick glance at both routes made us decide to choose the third option, which is an easy traverse from the col at GR205704 over to the grassy slope that’s beneath the rock overhang. It’s likely the slowest route but it facilitates an easy detour for water and I’d do the same again.

The Grey Corries are an amazing place to be in the afternoon and early evening light and the ridge walking is both easy and superb. Sgurr Choinnich Mor is one of my favourite peaks and I made a mental note of different places I’d like to come back to and bivvy. All along the ridge, the great rock architecture buoyed my spirits and, despite the fact it remained very hot and I was still feeling sick (plus a niggle I had from what I thought was a blister I needed to treat), I was feeling optimistic as we touched the summit of Stob Choire Claurigh and descended to Stob Ban, where is where we’d ended our first attempt.

It wasn’t long after this that the rails came off. Our ascent to Stob Ban was easy enough (I recall an enjoyable burst of energy as I climbed the last few steps to the summit) but the traverse over Meall A’Bhuiraich and our descent to Aibhainn Rath, now with head torches on, took what seemed like forever and we didn’t cross the river until just after midnight, again well behind a 24-hour schedule.

Part of the delay was, high up on Meall a’Bhuraich, the mild discomfort I’d had in the sole of my foot increased sharply and I’d eventually decided to stop and treat what I thought was the blister that was causing it. Foolishly, I’d left it until it was well past anything a Compeed could help with — my skin had badly macerated and had torn, almost de-gloving a portion of my foot, on the sole, right behind my toes, the wound down to the meat. The only thing we could do was dress it with medical gauze and some Durapore tape. This left me somewhat lame and the descent to the river and the long ascent to Sgurr Eilde Mor, coupled with the effort from the day and the continued heat into the night — it was ridiculously muggy — sucked away at my energy levels. My legs were still quite strong but my eyes were heavy and, after finally being sick (yeay), I could quite easily have slept standing up, leaning on my trekking poles. We decided to stop at the summit cairn for a break and, after just a few minutes, we were both fast asleep at 3am.