Blog

Occasionally, I like to write to complement my photography (primarily for myself but also with the outdoor community in mind). If I’m fortunate enough, and I’ve put the effort in, my thoughts make their way into print.

Patagon Journal interview

An interview with Patagon Journal, Patagonia's magazine for nature, the environment, culture, travel and outdoors.

I was pleased to be invited by editor Jimmy Langman to be a judge in the annual Patagon Journal photo competition. This was after the relationship I built with Jimmy following the publication of a trekking guidebook I wrote on Patagonia’s Los Glaciares National Park. The book itself is long out of print but the experiences I had when visiting Patagonia, the challenges and rewards of researching and writing a book and having it published and the contacts I made throughout have long lasted. The thoughts I provided below for the competition were published on the Patagon Journal website.

1. You wrote a guidebook to Los Glaciares National Park. What are some of your favorite places in the park to photograph and why?

My single favourite place to photograph in Los Glaciares National Park has been Glacier Fitz Roy Norte. Access to the glacier is via Paso del Cuadrado, a small pass high above Piedra del Fraile that leads to the remote west face of Cerro Chaltén and the frankly awesome 1600m high Supercanaleta, or Super Couloir (the route of the second ascent of Chalten, by Argentinian climbers Carlos Comesaña and José Luis Fonrouge, in 1965). If you don’t have the technical skills to be on a glacier, just visiting the pass itself provides you with mighty views. The great rocks walls of Aguja Guillaumet, Aguja Mermoz and Cerro Chaltén to your left and the three Torres - Cerro Torre, Torre Egger and Cerro Standhardt - are in front of you, the glacier far below. Paso del Cuadrado was not difficult to access when I last visited (crossing a glacier and cramponing up a steep frozen snow slope) but with warmer temperatures globally and the effect this is having on mountain regions, current conditions may mean it is more dangerous or challenging. Be confident in your mountaineering skills or I’d recommend you hire a local guide.

Not far behind Paso del Cuadrado in terms of mountain views I’d propose is Circos de los Altares, an even more remote glacial cirque that is situated beneath the ice-encrusted west face of Cerro Torre. Unless you’re a climber, and an expert one at that, the cirque is accessible only via a demanding trek up Marconi Glacier out onto the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap, a great ocean of ice sweeping west from the southern coast of Chile to its border with Argentina. Up to 650 metres thick and almost 13,500 kilometres square, the ice cap is said to be one of the largest expanses of ice outside the Polar Regions.

Both of the locations above appeal to me because of the challenge required in getting there. Add to this the spectacular views and they tick two important boxes for me as regards to what I'm passionate about in photography.

2. In the current edition of Patagon Journal you have a photographic essay about travel opportunities in Scotland. What are some of the challenges to doing photography in Scotland, and how does it compare to doing photography in Patagonia?

The hardest part I’d propose about photographing outdoors in Scotland (which is parallel to photographing in Patagonia) is managing the weather. Our maritime climates are very similar and unfortunately I’m no stranger to cold, wet or windy weather (often all three). I don’t crave bright blue skies - meteorological drama in the landscape adds immeasurably to your images - but when you’ve spent many days or weeks (sometimes months) planning a photo shoot and the weather is forecast to be sideways rain and strong winds, it’s difficult to a.) manage the disappointment it’s a personal project or b.) meet the brief if it’s a client shoot. We have to either go to plan B (always have a plan B) or reschedule.

3. What are some of your favorite places or things to photograph in Patagonia, and any plans to visit Patagonia soon? Where else do you want to photograph in Patagonia?

Regrettably, I’ve no current plans to revisit Patagonia (a recent potential trip to help promote the Los Dientes de Navarino circuit on Isla Navarino unfortunately didn’t come to fruition). I’d love to come back though, either with the goal of delivering a respected brand’s advertising campaign - the potential in Patagonia for inspiring the outdoor market is superlative - but I'd also like to support conservation activity in Patagonia from a photography and story-telling perspective, helping to reduce the impact we’re having on the environment and encouraging change (although I appreciate the contradictory aspect of that statement, given I live over 8,000 miles away in Scotland).

On a personal level, mountains are my passion and anything particularly rocky or snowy piques my interest (with glaciers and small mountain lakes being an added bonus). Locations in Patagonia I’d love to visit for photography include Cordillera Darwin - for Monte Sarmiento and Monte Bove - plus Perito Moreno National Park, home of Cerro San Lorenzo (I read many years ago about an adventurous trek which circumnavigates the mountain and it regularly resurfaces in my memory). An exploratory boat trip photographing the landscape around the fjords on the western coast of Chile would be awesome, as would the opportunity to be on the crew again to photograph the Patagonian Expedition Race (the locations the race director takes competitors into are amazing). The crowning glory I’m imagining would be a in-depth photo essay on one specific area, where I could cover the mountain and coastal landscape, key flora and fauna, the people who work there and are involved in its protection, plus those that play. In that regard, Kawésqar National Park in southern Chile holds great personal appeal.

4. You have specialized in outdoor photography for many years. What are a few of your most memorable moments and images in your outdoor photography career and why (Also, please explain a little of the backstory in your answer on what was happening at the time and how you got the shot)

My most memorable photos aren’t always those I’d class as being my best work (the initial image I’ve chosen was actually before I started as a photographer).

a.) Cerro Torre, Torre Egger and Cerro Standhardt from Circos de los Altares

Aside from the ‘firsts’ (first payment, first magazine publication, first cover, first advertising campaign), a particularly memorable moment - given it led to me starting my photography business - was having eight pages of pictures of Cerro Torre, Torre Egger and Cerro Standhardt from Circos de los Altares in a UK magazine called High Mountain Sports. The editor had been wanting to publish a Patagonia climbing special but the capricious nature of the weather had thwarted his efforts up until that point. Fortuitously, on a trek across the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap to camp in Circos de los Altares, we had perfect weather and I was able to share images that met the magazine's needs.

A photograph which led to me starting my photography business - Cerro Standhardt, Torre Egger and Cerro Torre from Circos de los Altares on the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap.

b.) Kayaking with dolphins during the Patagonian Expedition Race

Team East Wind sea kayaking with dolphins on the Strait of Magellan during the Patagonian Expedition Race.

The Patagonian Expedition Race is an adventure race par excellence held in the wilderness of southern Chilean Patagonia. Teams of four are challenged to navigate a remote 700km+ course, with minimal support, that demands advanced skills in the disciplines of mountain biking, trekking, mountaineering and sea kayaking. I captured this image as Team East Wind from Japan kayaked the Straits of Magellan ahead of their final 100km mountain bike into Punta Arenas. I was aware dolphins swam in the waters, having researched the history, flora and fauna of Patagonia thoroughly for the book I’d written on trekking in Argentina’s Los Glaciares National Park. I also had a feeling they would follow boats on the water, based on my understanding that dolphins are naturally inquisitive. It was a combination of this knowledge and, likely, some luck that led me to drive down a dirt road in a 4x4 along the shore as I followed the kayakers and waited for a dolphin to emerge. Every time one did, and sometimes there was more than one, a cheer arose from the team, their enthusiasm buoyed as they battled their way to a second place finish.

c.) Celebrating the dawn in Scotland

Charlie Lees early in the morning running on the Grey Corries ridge in the West Highlands of Scotland

The image I'd pictured in my head before this shoot was of a mountain runner navigating a ridge that snaked into the distance as the sun set far in the west over Ben Nevis, the UK's highest peak. I'd roped in a friend, Charlie, to help and we’d hiked up the mountain the previous afternoon so we were in a perfect position for the shoot. Unfortunately, as is often the case in Scotland, the weather didn’t play ball. The forecast was good but the light at sunset was muted by low-lying cloud and so we improvised instead, shooting a variety of shots until it got too dark. I wasn’t too concerned as we’d had the foresight to bring sleeping gear with us and we planned to spend the night on the summit so we could shoot again the following day.

The following morning, I awoke well before sunrise. I was disappointed to find the clouds were still there but a wild mountain hare, stationary not five feet from my head, buoyed my spirits. The hare and I sat in silence for a while, perhaps both of us just admiring the view, before it hopped away out of sight. My intentions were still to shoot facing west, catching my subject as the sun caught the ridge lines out to Ben Nevis. The view to the east though caught my eye and as the sun rose we turned around and focused on the opposite direction. As Charlie crested the summit, he leapt in the air slightly and I knew I had my shot. After a few repeat takes, including some without the leap, I was happy.

Capturing this image reminded me that it's best to keep an open mind and consider all options available to me when I'm executing a shoot. It also reminded me to keep an eye on an athlete’s natural traits and take advantage of them, when it’s appropriate, to produce a compelling image.

d.) Scotland 282 Munro Round Record Holder

Donnie Campbell running on the Horns of Beinn Alligin, in the North-West Highlands of Scotland

Scotland has 282 hills over 914.4m high (3,000ft) that are designated as Munros. Many if not most people (including me) take years or a lifetime to complete them all. Donnie Campbell is a running coach and endurance athlete from Scotland who, in 2020, ran all 282 peaks in just under 32 days, covering a total of 833 miles and 126,143m ascent (not including the cycling and kayaking he did to travel in between) to break the record at the time for the fastest completion of the Munros. This image, taken after the fact, showcases Donnie on the Munro Beinn Alligin in Torridon in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. It summarises what I particularly enjoy about photography - having the opportunity to illustrate someone’s athletic ability in the mountains.

e.) Backpacking Scotland's Munros

Alex Haken backpacking in the Mamores in the West Highlands of Scotland

One of the joys I find in backpacking (aside from poring over maps as you plan a trip) is staying up high in the mountains and walking right to the very end of the day, knowing you'll very likely be the only folk left on the hill. Many times over my hill-walking career I've experienced the solitude of being the 'last person standing' on a mountain. Backpacking has enabled me to camp on a number of high bealachs and summits in superb regions of Scotland such as Glen Torridon, Glen Coe, the Cairngorms and Glen Affric, as well as further afield in the Alps and Patagonia.

One of my favourite backpacking locations is the Mamores in the West Highlands of Scotland. Totalling 10 Munros (Scottish mountains over 3,000ft/ 914m high), the Mamores are grouped into 3 sets of hills, all easily tackled by a number of different routes. The central Mamores are characterised by narrow ridges, including the rocky arete on An Gearanach and the ominously named Devil's Ridge on Sgurr a'Mhaim. Shown here is us descending off the sweeping ridge of Na Gruagaichean one November, headed for a wild camp up high between An Garbhanach and Stob Coire a'Chairn. We had started our trip the previous day in Glen Nevis, planning to climb only three of the Munros but good stable weather meant we were able to continue over a fourth and put ourselves into position the next day for an easier round of the more well-known Mamore peaks that make up the Ring of Steall.

f.) Last light on the Scottish hills

Footprints in the snow at dusk during a winter hillwalking day out on Braigh nan Uamhachan in the West Highlands of Scotland.

This photograph is of a friend of mine, David Hetherington, as we headed along the snowy ridge of the Corbett, Braigh nan Uamhachan, in the West Highlands of Scotland. For pure satisfaction, it’s right up there with others in my portfolio, captured during a weekend that ticked many boxes for what I look for in a hillwalking adventure;

A night in my sleeping bag - We’d stayed the evening before at Gleann Dubh-lighe bothy, a stone building with a fireplace that the Mountain Bothy Association renovated in 2013 after it was accidentally burnt down)

A bluebird winter’s day hiking entirely on our own up a striking peak with a narrow ridge – We'd climbed first the 909m high Corbett, Streap, which is located right across the glen

Pure and simple hard work - After we descended 650m to the waters of Allt Coire na Streap we had a relentlessly steep 400m ascent back up to the ridge where we are in this photograph

Add in a setting sun, which we just caught before it dipped below the horizon, the fine view we had across to Ben Nevis, the UK’s highest peak (top left), and a descent by head-torch down a steep gully in the dark (lured by the thought of hot food and whisky back in the bothy to finish the day) and it had all the ingredients I like to look for when I’m planning a trip away in Scotland’s hills.

g.) Celtman Extreme Triathlon

Competitors heading pre-dawn towards the swim start of the Celtman Extreme Scottish Triathlon.

An iron-distance triathlon, Celtman is part of the XTRI World Tour series of races, of which Patagonman is also a fixture. This demanding race in the Scottish Highlands challenges competitors to swim 3.4km across a tidal, jellyfish-infested sea loch, cycle 202km on scenic highlands roads and then run a marathon 42km distance over two Munros on Beinn Eighe, both over 990m high.

Photographing Celtman means being up at 3am for the 5am swim start, driving the 202km cycle route in a 4x4 vehicle and then ascending 860m to run after and photograph the triathletes on this 3km long mountain ridge.

5. What advice do you have for aspiring outdoor photographers?

The following is an excerpt from a separate article I wrote about ‘Hints and tips for capturing great outdoor sports photography’.

The six things I would suggest to focus on are;

Know your camera

Shoot sports you know

Choose great locations

Prioritise good light

Try different angles

Focus on composition

Key takeaway -

Practice and master the above until it becomes second nature so you can free yourself up to focus on your creativity, seeking out moments which can help you to stand out from the rest

Appreciate that, other than exposure, there’s no real right or wrong. Try different things and see what happens. Take lots of shots and share them widely. Gather feedback and keep learning and, above all, enjoy the process.

6. What will you be looking for when deciding the winning photos of the Patagonia Photo Contest? What for you is the difference between a great photo and a good photo, for example.

Why someone proclaims an outdoor sports photograph to be a ‘great photograph’ is usually a personal thing but when I see an image that really captures my attention, it’s usually because two or more things have taken place;

People — A dynamic moment has been captured, usually in a creative way.

Place — The photographer has used an inspiring location that really connects me with the scene and helps me understand what’s going on (either a location I’ve not seen before or, if I have, they’ve photographed it in a unique way).

Lighting — They’ve made great use of natural or artificial light to bring the image to life.

I’ll have these three things in mind when I'm reviewing the submissions, which I'm looking forward to.

7. What are some projects you are working on right now, and what projects do you hope to do in the future?

My most recent efforts have gone into re-designing my website, adding new work that I plan to use to interest new clients. I'm hoping to have this launched before the end of March.

In the Spring, I'm looking forward to continue a mountain landscape photography project focusing on the Glen Coe and Lochaber region in Scotland, rounding out what I have already with images from lower down in the glens to produce a more complete representation of the area.

Adventure sports-wise, I've got a three trail and mountain running projects on the horizon, plus a specific mountain bike photography shoot planned, where I'm planning to use strobes to make the athlete really stand out from the landscape.

Visiting Scotland - From Chile or Argentina

Reasons for why people in Chile or Argentina may choose to visit Scotland for outdoor adventure instead of heading south to Patagonia and enjoying their own compelling landscape.

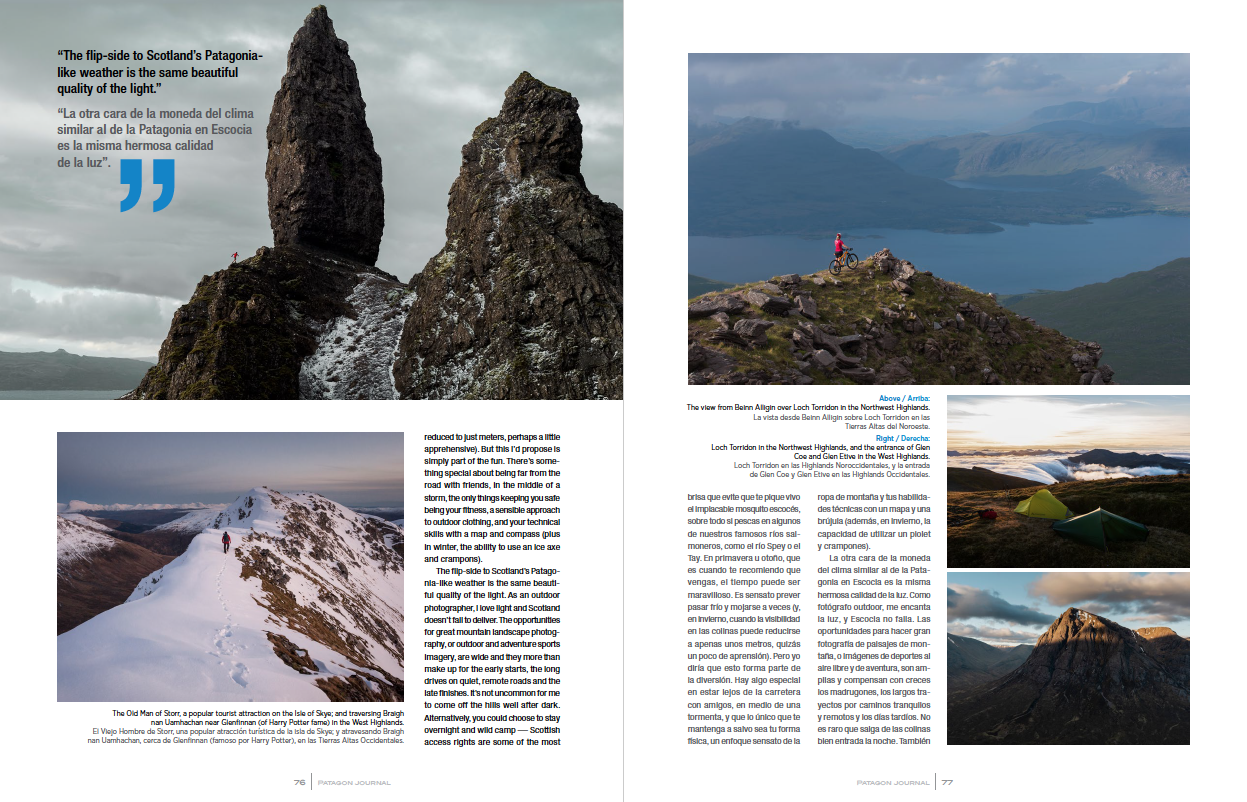

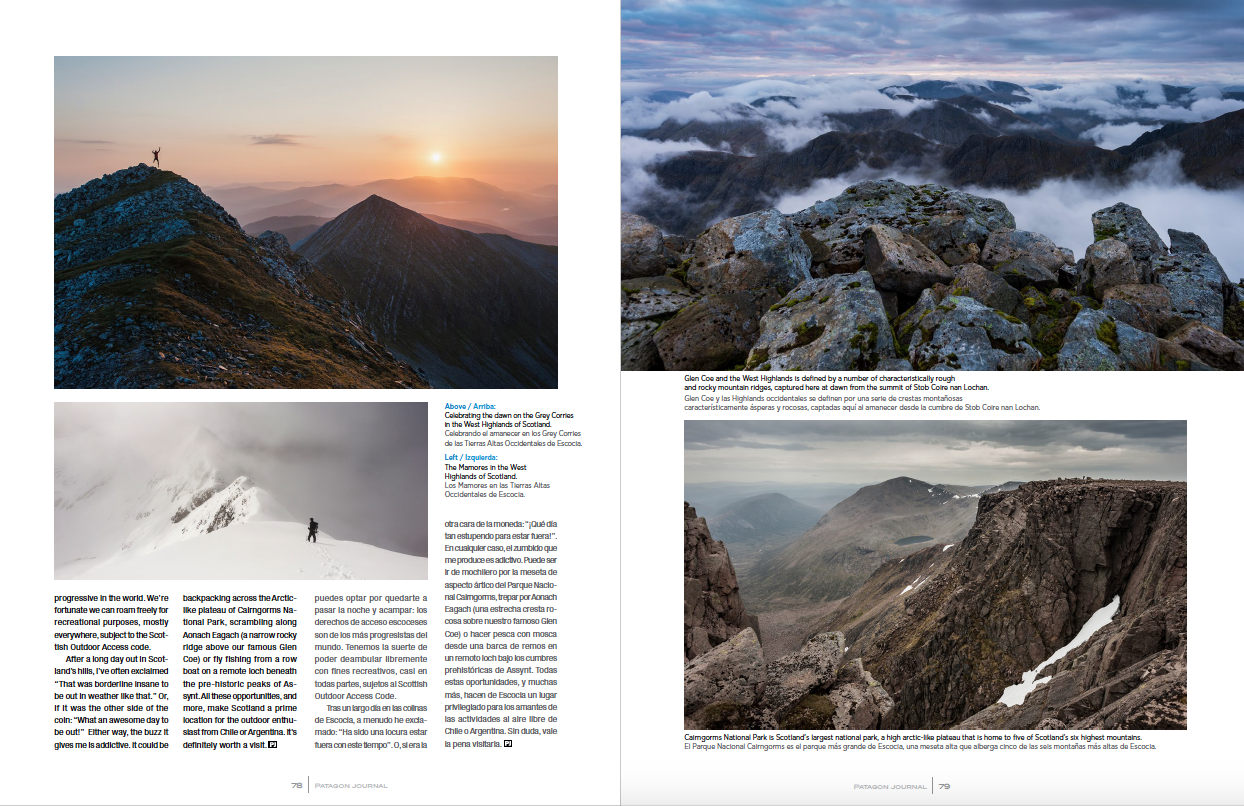

Written for and published by Patagon Journal - Patagonia's magazine for nature, the environment, culture, travel and outdoors. To support the launch of a new Destinations feature called ‘My Country’, I chose to focus on the rationale for why people in Chile or Argentina would choose to visit Scotland instead of heading south to Patagonia and enjoying their own compelling landscape.

(See also my Q&A with Patagon Journal)

Morning view from the summit of Ben Lui, a Munro in the West Highlands of Scotland

The rationale for visiting Scotland for an outdoor adventure is perhaps similar to the choices you’d make for travelling to Patagonia. Northern giants of Chile and Argentina aside, when viewed on a global scale, neither of our country’s mountains are the highest (Scotland’s tallest hill, Ben Nevis, is just 1,345m/4,413ft) but they pack a punch, offering the outdoor enthusiast a multitude of opportunities for a world-class mountain adventure — in Scotland’s case, without the skills or a guide needed for a venture onto Patagonia’s glaciers.

Running, hiking and mountain biking in the Scottish Highlands is my passion. Towards the end of each year, I’ll start to relish a Winter’s season walking and mountaineering. People often find this strange, because I’m not talking about the deeply cold, snowy ‘postcard’ Winter views you may get in the arctic countries, such as Sweden or Finland, but the bone-chilling, ‘just-above-freezing and the sleet’s blowing sideways’ maritime climate that myself and many other Scottish hillwalkers rejoice in (and which Patagonia aficionados will know all very well).

Scotland’s weather has a reputation for being wet, and sometimes harsh. Regular visitors to Patagonia will be used to that. In high Summer, the weather’s often warmer than expected but you’ll appreciate a breeze to prevent you being bitten alive by the relentless Scottish midge (especially if you’re fishing on some of our famous salmon rivers, such as the River Spey or Tay). In Spring or Autumn, when I’d recommend you visit, the weather can be awesome. It’s sensible to plan to be cold and wet at times (and, in Winter, when visibility on the hills can be reduced to just metres, perhaps a little apprehensive). But this I’d propose is simply part of the fun. There’s something special about being far from the road with friends, in the middle of a storm, the only things keeping you safe being your fitness, a sensible approach to outdoor clothing and your technical skills with a map and compass (plus in Winter, the ability to use an ice axe and crampons).

The flip-side to Scotland’s Patagonia-like weather is the same beautiful quality of the light. As an outdoor photographer, I love light and Scotland doesn’t fail to deliver. The opportunities for great mountain landscape photography, or outdoor and adventure sports imagery, are wide and they more than make up for the early starts, the long drives on quiet, remote roads and the late finishes. (It’s not uncommon for me to come off the hills well after dark). Alternatively, you could choose to stay overnight and wild camp — Scottish access rights are some of the most progressive in the world. We’re fortunate we can roam freely for recreational purposes, mostly everywhere, subject to the Scottish Outdoor Access code.

After a long day out in Scotland’s hills, I’ve often exclaimed “That was borderline insane to be out in weather like that”. Or, if it was the other side of the coin, “What an awesome day to be out!”. Either way, the buzz it gives me is addictive. It could be backpacking across the Arctic-like plateau of Cairngorms National Park, scrambling along Aonach Eagach (a narrow rocky ridge above our famous Glen Coe) or fly-fishing from a rowing boat on a remote loch beneath the pre-historic peaks of Assynt. All these opportunities, and more, make Scotland a prime location for the outdoor enthusiast from Chile or Argentina. It’s definitely worth a visit.

Runner’s World - ‘Rave Run’

Words and images published as ‘Rave Run’, a regular double-page spread which opens the popular Runner’s World magazine.

Various words and images published to illustrate ‘Rave Run’, a regular double-page spread which opens the popular Runner’s World magazine.

Rave Run - Cairngorms National Park

Rachael Campbell high above Loch A’an in Cairngorms National Park, Scotland

The location

Cairngorms National Park is home to five of the six highest mountains in Scotland. A network of paths join together summits and offer the trail runner plenty of opportunities for off-road, mountain fun. It’s not always essential to keep to paths. The Avon slabs (pictured) are nestled deep within the park. Alongside Shelterstone Crag, they oversee remote Loch A’an, a large freshwater loch 725m above sea level.

When to visit

Spring is a great season to visit. Remnants of snow will necessitate caution (and the right equipment) but, otherwise, often pleasant weather and the lack of the Scottish midge (Scotland’s famous but wretched biting insects) provides runners with positive returns.

Rave Run - Grey Corries

The experience

Charlie Lees on Stob Coire Chlaurigh in the West Highlands of Scotland

An ascent of Stob Choire Claurigh in the West Highlands of Scotland, at first on steep grass and then on broken quartzite, rewards runners with spectacular views. This vista, looking north-east at sunrise over the subsidiary top of Stob Coire na Ceannain, demonstrates the value of an early start.

The location

Stob Choire Claurigh is one of four Munros (Scottish mountains over 3,000ft) that make up the Grey Corries, a long, scalloped ridgeline that snakes its way south-west towards Ben Nevis, the UK’s highest peak.

A challenge

The Grey Corries form part of Ramsay’s Round, a challenge set by Charlie Ramsay in 1978 to run 24 Munros in 24 hours. A shorter version of Ramsay's round, which also includes the Grey Corries, is called Tranter’s Round. It is named after Philip Tranter, son of the novelist Nigel Tranter.

Rave Run - Liathach

The location

Liathach is one of big three mountain ranges in Glen Torridon (along with Beinn Eighe and Beinn Alligin) in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. Those with a head for heights will relish the challenge of the exposed scrambling across the top of the Am Fasarinen pinnacles to reach the Munro summit but an alternative route, that is much more runnable, is to find a high traversing path, which presents you with spectacular views across the glen.

The challenge

Munros are Scottish peaks over 3,000ft (914.4m) high. Numbering 282 in total, they offer adventurous trail runners a myriad of opportunities for mountain fun. Paths up steep sides provide access to ground such as the broad, Arctic-like plateau of the Cairngorms in the east to the narrow grassy ridges and rock that is more prevalent in the west. Conditions change quickly and it's wise to be prepared. Spare warm clothes and a map and compass for navigation, plus the knowledge to know how and when to use them, is essential.

Rave Run - Tarmachan Ridge

Joanne Thom on Meall nan Tarmachan in Scotland

The location

The Tarmachan ridge is a prominent viewpoint as you drive the A85 road towards the West Highlands of Scotland. Starting from the summit of Meall nan Tarmachan, a Scottish Munro 1044m high, the ridge winds its way south-west for 3.5km, over the shapely peak of Meall Garbh and beyond, offering great views north over Glen Lyon as you go. Take advantage of a car park at 450m, which takes some of the sting out of the initial ascent, or be a purist and start at the roadside 250m further down.

The challenge

Meall nan Tarmachan is within the boundary of Ben Lawers National Nature Reserve, which the National Trust for Scotland manages for conservation and public access. Home to seven Munros (Scottish mountains over 3,000ft/914.4m high), the reserve offers trail and mountain runners a variety of challenges, from a few hours to all day (or even overnight).

Rave Run - Black Cuillin, Isle of Skye

Donnie Campbell running on the Old Man of Storr in the Isle of Skye, Scotland

The location

Scotland’s Munro Round record holder, Donnie Campbell, approaches the rocky outcrop known as the ‘Old Man of Storr’ on the Isle of Skye in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. The 160-foot high pinnacle is part of the Trotternish Ridge, whose stunning, raw landscape has featured in several films, including The Wicker Man and Prometheus.

The run

You can run or walk up and down the Storr on a 2.3-mile trail. The foot of the Old Man is steep and a bit of a scramble, but once on the rocks surrounding the base, your reward is magnificent: panoramic views of the Sound of Raasay and the Scottish mainland beyond.

Sea kayaking and hillwalking in Scotland — Knoydart

An editorial feature for TGO magazine on the fun and benefits of sea kayaking to climb a mountain, instead of walking. Includes ideas on sea kayaking and hill walking route ideas.

Written for and published by The Great Outdoors, a UK outdoor magazine who advertise themselves as “the UK's leading authority on hillwalking and backpacking for over 40 years”.

High above Loch Hourn on the Munro, Ladhar Bheinn, in the West Highlands of Scotland

“My experience of 2 days of kayaking is that it’s knackering on its own”, my friend Kirsty replied to the email I’d sent asking her if she and her partner Steve were interested in a sea kayaking trip to climb a Munro (a Scottish mountain peak over 914.4m high). “But a hill thrown in? I’ll need to get training!”

As a photographer specialised in outdoor and adventure sports, I know a little about a lot of outdoor activities. I always endeavour to pick up hints and tips from athletes during photo shoots but, when it comes to sea kayaking, I’m still very much a beginner. Kirsty’s words therefore rang loud in my head as I focused on my technique and concentrated on energy-efficient paddle strokes as we left behind the tiny settlement of Kinloch Hourn on Scotland’s remote west coast and headed out on a two-day sea kayaking adventure to climb the Munro, Ladhar Bheinn.

Ladhar Bheinn, 1020m tall, is one of my favourite Scottish mountains. Partly, because it is only accessible by boat or by foot. Getting to the peak involves travelling 9km by boat from Mallaig to Inverie (popularly known as being the home of Scotland’s most remote mainland pub) or hiking c.13km of rough terrain from Kinloch Hourn (itself a 35km drive along a single track road).

Most visitors looking to climb Ladhar Bheinn from Kinloch Hourn will hike in. The idea for a sea kayaking approach came to mind two months previously, during a particularly gruelling mountain backpack through deep snow in the Cairngorms National Park. Conversations that usually focused on the joys of light packs in Summer and afternoons soaking up the sun outside an alpine hut turned to the potential for a waterborne approach to climb some of the hills on Scotland’s very Patagonia-like west coast.

At the time, a discussion on the merits of kayaking into a mountain was just a means of taking my mind off the weight of a winter backpack on my shoulders and freeze-dried food in my belly. Fast forward to May 2016 and we’d made it a reality. Kirsty, Steve and I were joined on our Ladhar Bheinn adventure by Ben Dodman, a professional sea kayaking instructor with Rockhopper Sea Kayaking, a Corpach-based business near Fort William that offers day and overnight trips. Kirsty and Steve had been on trips with Rockhopper before and, when we approached Ben with the idea, he was keen to come along.

“There’s no real need for lightweight sea kayaking”, Ben had said when I’d asked him if it was worth limiting the camping equipment I’d planned to bring with me. “A kayak carries a lot of gear so you don’t have to skimp on the nice-to-have’s”. Kirsty and Steve — our volunteer cooks for the weekend — demonstrated similar principles in the menu they had prepared. Not the usual backpacking fare but pancakes, honey and banana for breakfast, fresh salad vegetables, tomatoes, wraps, tuna fish and mayonnaise for lunch and pasta, home cooked tomato, vegetable and chilli sauce and freshly-baked muffins for dinner. The latter three to be washed down with fine Italian wine. It had all the makings of a great weekend.

As we paddled Loch Hourn, the water’s translation from Gaelic, the Devil’s Loch, became apparent. One of the benefits of sea kayaking is it allows you to get close to nature. Kayakers on the west coast of Scotland have reported sightings of otters, seals, basking sharks, all habitual visitors to our islands and, on occasion, orcas. Shooting down the loch, metaphorically speaking, taking advantage of the tide and wind, we saw no sign of life. Nothing in the water nor in flight above the steep slopes either side of the water. We didn’t mind though, as dominating the view, partially covered in cloud, was the lower slopes of Ladhar Bheinn.

Sea kayaking on Loch Hourn in front of the Munro, Ladhar Bheinn, West Highlands of Scotland

I’d climbed Ladhar Bheinn twice before. My first time was via likely the most popular route up the mountain, from the small settlement of Inverie. We’d headed first for Mam Barrisdale before breaking off up steep, fern-covered slopes onto the curious feature of Aonach Sgoilte, or split ridge. My second ascent was during a 4-day backpack of all the Munros in Knoydart, when we reached Aonach Sgoilte after first climbing two nearby Corbetts, Beinn na Caillich and Sgurr Coire Choinnichean. Both times were in excellent weather and we could see all around as we continued up the scrambly north-west ridge of Ladhar Bheinn to its summit.

The classic route up Ladhar Bheinn is to follow a horseshoe around Coire Dhorchail. The headwall of this great mountain corrie is ringed with crags and it is enclosed by two great, narrow, steep-sided ridges, Stob a’Chearcaill and Stob a’Chiore Odhair. As we crossed Barrisdale Bay, we could see right into the corrie. The wind caused the chop on the water to increase as we headed into more exposed waters — the bay opens out into the Sound of Sleat offering access to Glenelg, Inverie and more — and care was needed as we negotiated a stiff cross-wind. Barrisdale bay however is not big and we soon reached the shelter of the shore and looked for a place to stay the night.

Outside the comforts of Inverie, there are three overnight options when you climb Ladhar Bheinn. You can wild camp almost anywhere, courtesy of Scotland’s refreshing outdoor access code, or stay in one of two private bothies nearby, Barisdale bothy or Druim bothy. Neither bothy is maintained by the Mountain Bothy Association and both charge a fee for staying at their accommodation. Barisdale however has the advantage of not needing pre-booked.

“Keep an eye out for a place to camp”, shouted Ben as we kayaked along shoreline. (I’d learnt that normal conversation was quite difficult on a kayak, soft-spoken words far too easily getting whipped away on the wind). We’d agreed as a group that we should take advantage of travelling in sea kayaks and wild camp on the shores beneath Ladhar Bheinn, only taking advantage of the bothy if the weather was really bad, After a short paddle, Ben found a suitable spot in a sheltered bay and we beached the boats safely away from the tide, pitched camp and ate a quick lunch.

Sea kayaks lying beside a tent on the shores of Loch Hourn beneath the Munro, Ladhar Bheinn, West Highlands of Scotland

Despite the fact we’d started paddling at an early hour, there wasn’t much daylight left when we started our ascent of Ladhar Bheinn. From our campsite, there were a few routes we could have taken up the hill but we really wanted to do the classic route, via Coire Dhorrcail. To reach the corrie from our campsite involved a 2.5km traverse along the coastline, which involved some fun, but slippery coasteering and a river crossing. This made for an interesting start for our ascent, but it wasn’t long before we’d left the waters behind, gained some height and entered the mouth of the corrie.

“What an awesome location”, I shared with Kirsty as we followed Ben and Steve further into the corrie. I had envisaged a natural mountain amphitheatre and the terrain didn’t disappoint. As well as its steep outer sides of Stob a’Chearcaill and Stob a’Chiore Odhair, Corrie Dhorrcail has two mini corries within it, separated by a steep rocky nose. It’s quite a special place.

Scrambling up to the summit ridge on Ladhar Bheinn, a Munro in the West Highlands of Scotland.

Scrambling on route to the summit of Ladhar Bheinn, a Munro in the West Highlands of Scotland.

Ascending the summit ridge on Ladhar Bheinn, a Munro in the West Highlands of Scotland

In 1999, Knoydart had a burst of media attention when the local community raised £850,000 to purchase the land from the then estate owners. The east boundary of what became the Knoydart Foundation’s land (www.knoydart-foundation.com) ran along Ladhar Bheinn’s north-west ridge and, three or so hours after we had left the kayaks, we crested the headwall of the corrie and broke out onto this ridge near the summit of Aonach Sgoilte. The Knoydart peninsula is known as the ‘rough bounds’ for the wild nature of its terrain but we hadn’t found the ground so far too bad and had gained height relatively quickly. We had however been sheltered by the corrie headwall from the prevailing wind. As we stood on the ridge looking up towards the summit, we were more exposed and we quickly donned the extra clothing and waterproofs needed to keep warm as the wind whipped ominous-looking clouds across the steel-coloured sky. It was clear we were going to have some squally, windy weather on our way to the summit. To reinforce this fact, when we looked down to Loch Hourn ‘white horses’ had already started a race across the water all the way back east towards Kinlochourn.

Despite the somewhat bleak weather, we were enjoying ourselves. Ladhar Beinn’s summit flanks are a fantastic viewpoint and, as well as the view to Loch Hourn, we could see south-east to its neighbourly Munros, Luinne Bheinn and Meall Bhuide, and west out over the Corbett of Sgurr Coire Choinnichean towards Mallaig. Ladhar Bheinn’s north-west ridge is also great fun. It’s quite rocky and there’s a handful of scrambling on it, grade 1 at most, but nothing overly technical or exposed. (You can though stand on an obvious prow of rock halfway up that overhangs a drop of several hundred feet. It makes for a great photo opportunity).

Looking down to Loch Hourn during an ascent of Ladhar Bheinn, a Munro in the West Highlands of Scotland

I was almost disappointed when we climbed the last of the summit slopes and joined up with the connecting ridge that goes out to Stob a’Chiore Odhair. All that was left was an enjoyably airy walk that took us across Ladhar Bheinn’s final summit ridge and on to its summit cairn. As is all too often the case on Scotland’s mountains, we didn’t hang around for too long. Rain had been falling for most of the previous hour and thoughts of being back at camp eating dinner had started to cloud my thought process. (This was despite the banana and walnut muffins Kirsty had produced out of her rucksack on the way up. “There’s enough for two each if you want them”, she triumphantly proclaimed. There was definitely little concept of ‘light and fast’ on our trip and, I must say, it was all the better for it).

It was after 5.30pm when we started our descent. Despite not having to go back to our starting point at Kinloch Hourn, we still had a fair way to go to get back to our tents. The decision we’d made was to reverse our steps back along the summit ridge and then complete the horseshoe of Coire Dhorcaill by a descent of the mountain via Stob a’Chiore Odhair. One of the benefits of wild camping is you’re not restricted to existing routes up or down mountains and, as we descended the ridge, which is enjoyably narrow, we realised it made sense for us to break off towards Bealach a’Choire Odhair. After a few steep descents, we could see our tents below and we headed straight down to the shores of Loch Hourn. All that was left was a final short burst of coasteering before we reached our tents, the stoves were lit and dinner was served as we sat on our kayaks and watched it get dark.

Paddling Loch Hourn on our route out from the Munro, Ladhar Bheinn, in the West Highlands of Scotland

Planning a sea kayaking trip

Whilst our paddle on the way to climb Ladhar Bheinn was greatly assisted by the outgoing tide, our journey the next day back to Kinloch Hourn was needlessly harder as we paddled through the narrows at Caolos Mor straight into the tide (only because everyone was kind enough to stop in Barrisdale Bay so I could take some photos for this article). Paddling against the flow of the water is hard work and, energy-wise, it meant we all had to work at least 2 times harder than if we were going with the flow. It makes much more sense to plan a sea kayaking trip around the tide. If you don’t know how to do this, go with a professional. Rockhopper Sea Kayaking (www.rockhopperscotland.co.uk) is based in Corpach, near Fort William, and offers half, full and multi-day sea kayaking trips through ‘some of the most spectacular coastal, mountain and island scenery in Scotland’. All you need to do is turn up and play.

Basic sea kayaking equipment

Wet or dry suit

Sea kayak

Spray deck

Buoyancy aid

Paddle

Map (For Ladhar Bheinn we used OS Landranger 33, Loch Alsh, Glen Shiel and Loch Hourn)

Compass

Nice to have;

Dry bags (lots of them)

Rubber shoes

Hat and gloves

Tow belt

Spare paddle (at least one between a group)

Waterproof camera case

Other kayaking / hillwalking trip ideas in Scotland

Loch Quoich / Ben Aden

Loch Scavaig / Skye Cuillin

Loch Veyatie / Suilven

Loch Mullardoch / Benula Forest

Loch Monar / Monar Forest

A four-day trek around Fitz Roy — Los Glaciares National Park, Patagonia

Adventure trekking on the glaciers beneath Cerro Fitz Roy in Los Glaciares National Park, Patagonia.

Published in Sidetracked magazine, Patagon Journal and UKClimbing.com

The 1600m high Supercanaleta on the west face of Cerro FitzRoy

“It’s called the Guillaumet pass. It’s generally used by climbers. There’s a little crevasse danger but as long as the weather holds it’d be fine. You’d be right underneath Monte Fitz Roy.”

The e-mail I’d opened was from a 29-year old Argentinean mountain guide, Pedro Fina. I’d first met Pedro in 2004, when he was one of two guides I’d had on a 4-week trekking expedition in South America. During that trip, we’d climbed a glacier beside two of the great peaks of the Patagonian Andes, Monte Fitz Roy (Cerro Chaltén) and Cerro Torre, and traversed a small portion of the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap, a flat expanse of thick ice — 13,000km2 — that flows west from the mountains and down into the Pacific Ocean.

My objective this year was to get much closer to the mountains, to scratch an exploratory itch I have for Patagonia and to research new treks for a guidebook I was writing to Argentina’s Los Glaciares National Park. With the help of Pedro and Rolando Garibotti, a US-based Italian-Argentine mountain guide and an expert on Patagonia climbing, I’d settled on a shorter expedition around Monte Fitz Roy, connecting small cirques and climbers’ trails with pocket glaciers and high bealachs to create a trek that I hoped would offer me the finest views possible of the Fitz Roy massif.

“I’ll pick you up at 7am. There’s a 3–4 day good weather forecast and we should take advantage of it whilst we can.”

I’d only been in Argentina a day when Pedro suggested we should leave the following morning. Neither of us had any desire to be caught out in a Patagonian storm. The weather in Patagonia is commonly said to be amongst the worst in the world. Gregory Crouch, in his book, ‘Enduring Patagonia’, describes how dark storm fronts that begin life deep in the Pacific Ocean rampage across the sea uninterrupted, the cold and wet air picking up moisture and gaining in speed as it heads towards a thick belt of low pressure, termed a circumpolar trough, ringing Antarctica. When this trough has expanded over Patagonia, as is all too often the case, the storms are dragged kicking and screaming over the Andes first. It is not uncommon to encounter wind speeds of 160 kph. When this is the case, the last place you’d want to be is up in the mountains where, as Greg quotes US climber Jim Donini in his book, “survival is not assured”.

It was this sobering thought that occupied my mind when, two days later, Pedro and I stood atop the 1700 m high Paso del Cuadrado and prepared to descend 400 m of blue, translucent ice to reach the remote and heavily-crevassed glacier we could see far below us.

We had climbed the 200 m to Paso del Cuadrado that morning, after ascending 1000 m the day before from a private campsite just outside Los Glaciares National Park and spending a dry, cold night beside a huge, black rock called Piedra Negra. Two of Pedro’s friends spent the night with us, shivering without sleeping bags as they waited to attempt a nearby peak, Aguja Guillaumet.

By 11.00am Pedro’s friends could be a world away. Having carefully descended the ice slope we’d swapped crampons for snow shoes and headed uphill towards the Fitz Roy Norte Glacier. A huge jumble of ice towers, or seracs, spilled out of a higher basin as the glacier broke up and made its way down valley. Giving this icefall a wide berth we traversed instead beneath a jagged bergschrund that had formed as the ice had torn itself away from the huge granite walls of Aguja Mermoz. Rock-fall was a distinct possibility and more than a few deep breaths were taken before we passed the seracs and could cut back onto the upper part of the glacier. As we did so, everything underfoot turned to pristine white.

Perhaps it was the uncommon lack of wind and the resultant silence or more likely my jangly nerves, but the further I walked into this glacial cirque the more the surroundings began to affect me. It wasn’t just that we were far from civilisation — a 2 day walk to the small town of El Chalten unless you could climb expertly — but that if you had seen us we would have been impossibly small. Behind us was the 400m ice slope we had just descended. We had to climb it again later in the day. To our right was a vast wall of ice-clad cliffs, 200 m high, which made up the southern side of Cerro Pollone and Cerro Piergiorgio. Beyond these cliffs was the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap, beyond that only the Pacific Ocean. In front of us was the fourth ‘wall’ of the cirque, the Filo del Hombre Sentado, or Sitting Man Ridge. At the top of this ridge the ground dropped 700 m to the Torre Glacier before it rose up the other side again to form a 3 km long incisored skyline of agujas, or needles, that culminates in three of the most recognisable and difficult to climb mountains in the world — Cerro Torre, Torre Egger and Cerro Standhardt.

Clearly visible from the ridge is the most popular route up Cerro Torre; the so-called Compressor Route, named after the Italian climber, Cesare Maestri, who drilled over 400 bolts into the mountain as he climbed it in 1970. Despite the prevailing weather, and the outcry of many a traditional climber, the bolts are still there, as is the drill itself. It is tolerated by many of today’s climbers as an opportune place to stand on an otherwise blank vertical wall. Maestri’s original claim to have summited the mountain in better style, in 1959, up the far harder north-east ridge, is still a subject of much debate. This route was not climbed without suspicion until 2005, by the afore-mentioned Rolando Garibotti and two Italian friends, Ermanno Salvaterra and Alessandro Beltrami. Rolando is one of many people who believe, not without reason, that the first people to climb Cerro Torre were a team of Italians, in 1974, via the west face.

All views paled into insignificance however by the massive, 1600 m high flange of granite that rose up on our left. Monte Fitz Roy’s huge west face is split in two — as if by a mighty axe blow — by the majestic Supercanaleta, or Super Coulouir.

If you’re the (sadly late) American climber, Dean Potter, this 60 degree, ice-filled couloir is regarded as an easy way up the mountain. In 2004, Potter raced from the bottom of the couloir to the summit of Fitz Roy, all 1600m of snow, ice and rock, in a mere 6 hours 29 minutes. He then descended the other side of the mountain the same day. In 1965, the first ascensionists of the couloir, Argentineans Jose-Luis Fonrouge and Carlos Comesana, took a more realistic 2 days, before they descended on their third day through a storm that raged around the mountains for a staggering 36 days. You can be sure this thought wasn’t far from my mind as I considered the meagre two days rations I had packed in my backpack.

“The next bit’s got the crevasses”, Pedro said, as he handed me my obligatory fix of morning coffee. “Great”, I said, but I didn’t really mean it. Although it was possible for us to have abseiled the Sitting Man Ridge and descended the Torre Glacier back to El Chalten this was outside the realms of my experience and we had chosen instead to return to Piedra Negra. It was from here that we were headed for Paso Guillaumet, a small notch in the mountains that enabled access across the east-west divide, and from there to another high mountain pass, Paso Superior, that lay right in front of Monte Fitz Roy. Both Pedro and Rolando had told me in their e-mails that the view between these passes was spectacular.

The ground up to Paso Guillaumet was similiar to the previous day; long, steep ice slopes broken up by the odd rock outcrop that we took advantage of for snack breaks. Higher up, we entered a gully system until a large, angular rock blocked the way and we were forced to move out onto a buttress for a few easy pitches of easy rock-climbing.

On reaching the pass the view opened out to the east and we could see far below us, out over the glaciers to the dry, brown Patagonian steppes and the stone-gray waters of the enormous Lago Viedma. My eyes kept darting back and forward between the contrast of the brown steppes in the distance with the whiteness of the ice cap we could see over to the west.

Once we crossed the watershed we headed up towards a rock apron that made up the lower eastern face of Aguja Guillaumet. Traversing the base of this mountain we passed the Amy Coulouir, a narrow ice hose that offers a popular way to the summit. It was this route that Pedro’s friends had taken the day before. The jagged rent of a bergschrund and other crevasse danger eventually caused us to head away from the mountains and descend towards a large, snow-covered plateau that is only hinted at from the usual treks near El Chalten. As we neared the plateau, Pedro wasn’t happy with the route we had taken and he walked back towards me, motioning for us to find another way to descend. As we did so, I looked back up to our right and could see our footprints on top of a huge, overhanging ice cliff. The gap that had opened up beneath it was big enough to swallow a house.

Once on the relative safety of the plateau, I could finally appreciate the view. The magnificent east face of Monte Fitz Roy was only half a kilometre away. It’s impossibly huge and I still can’t imagine anyone having the courage to climb it. Even to reach the bealachs either side of the peak involves 300 m of technical climbing — and the summit is still another 1,000 m higher. It was first reached in 1952, by the Frenchman, Lionel Terray, and his partner, Guido Magnone. It took their expedition many weeks to reach the top and a lot of time was spent burrowed underground in snow caves waiting out bad weather.

At the far end of the plateau, making up the southern end of the Fitz Roy skyline, was the huge granite tooth of Aguja Poincenot. The English mountaineer, Don Whillans, was the first person to climb this peak, joining a team of Irish climbers in 1957 who attempted the mountain on a Guinness sponsorship. Their descent of the mountain was hampered by strong winds and it was 20 hours before they reached the safety of their high camp at Paso Superior. When they did so they were exhausted — Pedro said this reminded him of when he and his friends had climbed the mountain in 2003; they were so tired they kept sitting down and falling asleep during their descent.

Our own traverse to Paso Superior was uneventful, if nerve-wracking. Dropping off the plateau onto a steep snow slope, we traversed above an intermittent line of blue-black crevasses that threatened to catch any fall. It was easy terrain but after two days of steep ice slopes, seracs and crevasses my nerves were frazzled and I just wanted to be on solid ground. I got my wish when, just below the pass, we encountered a 10 m rock wall with a flotsam of old fixed rope and a rope ladder that hung loosely down the rock. With no desire to put any weight on the trashed ropes I cIimbed a mixture of rock and ladder and pulled myself up over the top and out onto Paso Superior. It was empty, except for a large climbers’ haulbag sitting on the snow.

The plan had been to stay at Paso Superior for one night, using one of the existing snow caves or digging a new one, before descending 1,000 m down the glacier the following morning to reach Laguna de los Tres. This small lake at the foot of the glacier is the usual high point for trekkers in the national park. It has great views of the Fitz Roy mountains, especially in the early morning. I should have been looking forward to it. But on the plateau I’d decided I’d had enough. Enough steep snow and ice slopes. Enough thoughts of falling into a crevasse and dying a cold and unpleasant death. Turning the sight of some grey, wispy clouds I’d seen forming over Fitz Roy into the leading edge of a storm, I asked Pedro how long it would take us to get down to Laguna de los Tres. “2, maybe 3 hours?” he replied, “then another 30 minutes to Campamento Poincenot. Oh, plus another hour to get back to the car.” “What’s the ground like?”, I asked, immediately deciding it was worth it, regardless of the terrain. “Do you want to leave now?” he replied, giving me that quizzical look talented folk give you when they just don’t understand. “Yeah, I’ve got a book to write”, I said, adding “And the weather’s got to turn sometime”. “Okay” he replied, “let’s get moving. If we hurry we’ll make it all the way to El Chalten.” And with that, we packed up and headed for home.

Southern Patagonian Ice Cap Traverse — Los Glaciares National Park, Patagonia

Ice trekking across the vast polar-style landscape of the Hielo Continental, or Southern Patagonian Ice Cap.

Published in Patagon Journal - An overview of a six-day trek onto one of the largest expanses of ice outside the Polar Regions.

It’s 4am. I put on all my clothes and go outside to help dig our tent out of its snow grave. I try to ignore the view around me — because this is the second time I have been up through the night and because it is cold and very, very windy. This is Patagonia, after all.

Ducking back into my tent, I can’t help but glance across the huge expanse of ice we’re camped upon, the Hielo Continental, or Southern Patagonian Ice Cap. Silhouettes of spectacular mountains slice into the sky. The largest peak in view is the snow-covered Cerro Lautoro, an active volcano, sulfur fumes rising from its top and mixing with clouds which stream from its summit ridges. The peak is 35km away but seemingly close enough to touch. Behind Cerro Lautaro there is more of the same — ice and mountains — until the ice cap melts into the Pacific Ocean, 30 kilometres further on.

The Southern Patagonian Ice Cap is a great ocean of ice sweeping west from the southern coast of Chile to its border with Argentina. Up to 650 metres thick and almost 13,500 kilometres square, it is said to be one of the largest expanses of ice outside the Polar Regions.

Icy wastelands such as the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap, not without reason, are usually out of bounds to ‘normal’ people. But short trips onto the ice are possible, with the services of a guide, in Argentina’s Los Glaciares National Park.

Peaks in Patagonia’s Los Glaciares National Park don’t have the high altitude of the Himalaya to define their difficulty. But they rear up incredibly steeply out of an otherwise flat landscape. Cerro Fitzroy dominates the area, by virtue of its sheer size and bulk. Standing 3,441m high, it soars above its neighbours, spouting out glaciers and satellite crests that overshadow everything except the Torres Range, a collection of needle-like spires 7km south. Undisputed queen of the Torres is Cerro Torre, the Tower Mountain. It rises vertically to 3,128m in height and has long been regarded as one of the most plum mountains in the world to climb (its neighbour, Torre Egger, being termed as the hardest). This is not because of the altitude or highly technical climbing, but by virtue of its location — Cerro Torre stands sentry for the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap, located right on its edge. Described by the South Tyrolean climber Reinhold Messner as “a shriek turned to stone”, the mountain receives the full brunt of the prevailing weather. The typically maritime conditions, accompanied by high winds, regularly sees Cerro Torre and its adjacent peaks covered in a maelstrom of moisture-laden, grey-coloured storm clouds, which, when they release the peaks, leave them topped in a rime of perilous, and at times unclimbable, snow and ice ‘mushrooms’.

Most visitors see Cerro Torre from the east. A comfortable two-day journey takes you from Buenos Aires to El Chalten, where you can step into the view found in postcards all over the park’s gateway town of El Calafate. Less common — and a world away in terms of the memories you’ll come away with — is to ascend Marconi Glacier and trek south on a traverse of the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap, to a remote glacial cirque called Circos de los Altares. Here you can gape, mouth wide open, right underneath Cerro Torre’s cathedral-like proportions.

Not everyone who attempts the Patagonian Ice Cap traverse reaches Circos de los Altares. The biggest obstacle is the weather. Strong winds, which have been termed locally as Escobado de Dias, God’s Broom, are generated far out in the Pacific Ocean. Known to gather speeds of up to 200 kilometres per hour, they race across the flat surface of the ice cap and hit the mountains with great force. Any visitor to the cirque, or climbing high on the mountains at this time, is at the complete mercy of the weather gods.

Another obstacle to a successful traverse of the ice cap is crevasses, both on Marconi Glacier and at the mouth to Circos de los Altares. One of these crevasses, 30 metres across, even has a name, La Sumidero. Crystal clear water arrives in this spherical ‘sink’ before swirling counter clockwise and disappearing down a great black hole which would easily swallow a man. Then there’s your pack size. Potentially nine days round trip from El Chalten requires a lot of food and equipment and you’ll analyse the contents of your rucksack like never before. ‘Light is right’ is the mantra for any such trip and your toothbrush may not survive being in one piece.

Most people require the services of a mountain guide for the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap. You can use one of the local companies or hire a guide direct. I used Pedro Augustina Fina of Argentina. He’s a nice bloke, greyhound fit, with a naturally friendly smile. The trick is to slow him down with much of the gear, and to use your gas canisters first. He’ll be wise to that though. Pedro travels each year to El Chalten early, from Buenos Aires, to do some mountain climbing before the guiding season starts. He’s summited Mount Fitz Roy, as well as Aguja Poincenot and Aguja Guillaumet, two serious peaks either side of Fitz Roy, and once spent two days in a snow cave hiding out the weather on an ascent of Cerro Lautaro. On a different trip he took me on a partial circumnavigation of Mount Fitz Roy. But that’s another story.

About the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap Traverse

Summary

Los Glaciares National Park is a UNESCO world heritage site in Patagonia at the tip of South America. It is named after the multitude of glaciers that flow east from the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap, a great ocean of ice sweeping west from the borders of Los Glaciares National Park to the southern coast of Chile. The ice cap is up to 650 metres thick and almost 13,500 kilometres square and is said to be one of the largest expanses of ice outside the Polar Regions.

About the trek

A full traverse of the Southern Patagonia Ice Cap is a major mountaineering expedition. For lesser mortals, week-long treks from El Chalten are possible with the assistance of local mountain guides.

This demanding trek/expedition is a fantastic and possibly unique adventure that circumnavigates the Cerro Fitz Roy and Cerro Torre mountain ranges by way of the Southern Patagonia Ice Cap. It gives the experienced trekker the opportunity to experience polar-type exploration as they travel across compact pack ice on snowshoes, towing their belongings behind them on a sled. The highlight of the expedition is an overnight camp in the glacial scoop of Circo de los Altares, the Cirque of the Altar. This great mountain cirque, originally termed ‘Hunger Valley’ but rechristened in 1974 by the first mountaineers to scale Cerro Torre, stands many kilometres from its two nearest exits to the ice cap; Paso Marconi and Paso del Viento. The remoteness of the cirque from these passes, and from the relative safety of El Chalten, is heightened by the sheer, kilometre-high west faces of Cerro Torre, Torre Egger and Cerro Standhardt, towering above the cirque floor.

Starting point

The village of El Chalten in Argentina

Total distance

60–70km

Time required

Minimum 6 days

When to go

November to April for the Patagonia Autumn / Spring / Summer

In Rigorous Hours - Scottish Winter hillwalking

A photo essay in The Great Outdoors magazine championing the Scottish Winter season for hill-walking and scrambling.

Published as an eight-page spread in The Great Outdoors magazine

On a global scale, Scotland's mountains may not be very high (our tallest mountain, Ben Nevis, is only 4,409ft) but they pack a lot of punch and together they offer the outdoor enthusiast almost unlimited opportunities for a top-class mountain adventure.

Moving upwards in a blizzard near the summit of Mayar in Cairngorms National Park, Scotland

Towards the end of each year, I'll turn my attention from summer hiking and biking and start to look forward to a winter's season spent walking and mountaineering in the Scottish Highlands. Folk often find this strange because I'm not talking about the deeply cold, snowy 'postcard' winter of, say Alaska, but the bone-chilling, 'just-above-freezing and the sleet's blowing sideways' maritime climate that myself and many other Scottish hillwalkers rejoice in.

Yes, the Scottish Winter season can be harsh and miserable, and on occasions dangerous. You'll very likely be cold and wet. And sometimes scared. But I think that is part of the fun. There's something special about being far from the road with friends, high up on a scoured plateau in the middle of a winter storm, the only things keeping you safe being your fitness, a sensible approach to outdoor clothing and your technical skills with map, compass, ice axe and crampons.

The flip-side to Scotland's wild Winter weather is the quality of the light. As a photographer, I love light and winter offers some of the best light there is. The opportunity to capture great action shots more than makes up for the early rises, the long drives on quiet, remote roads and the late finishes (we're usually not getting off the hill until well after dark).

On occasions, when I've got back to the car, I've felt, “that was borderline insane to be out in weather like that”. Or, if it was the other side of the coin, “that was awesome day to be out!”. Either way, the buzz it gives me is addictive. Whether it's a short walk up my local hill in the snow, a long day out on the Arctic plateaus of the Cairngorms or a more challenging ascent of a narrow ridge in the West Highlands, I think Scotland offers something for everyone during the winter. I'll look forward to seeing you on the hills.

‘My Favourite Hill Photo’ — UKHillwalking.com

A submission on request of UK Hillwalking, describing a favourite outdoor adventure photograph.

Requested by UKHillwalking.com. You can view all contributors’ submissions in UK Hillwalking’s ‘My Favourite Hill Photo’ article.

Footprints in the snow at dusk during a winter ascent of Braigh nan Uamhachan in the West Highlands of Scotland

In 2020, Dan Bailey of UKHillwalking.com kindly invited me to submit an image and some words for a feature they were running to share with their readers their “leading contributors” ‘favourite hill photo’.

It’s always difficult to choose one image you like best. Technically, I don’t think this is the best photograph I’ve ever taken (it’s of my friend David Hetherington, as we head along the ridgeline of the Corbett, Braigh nan Uamhachan, in the West Highlands of Scotland). But for pure satisfaction looking back, it’s right up there with others in my portfolio. It reminds me of a weekend that ticked many boxes of what I look for in a hillwalking ‘adventure’. A night in my sleeping bag (we’d stayed the evening before at Gleann Dubh-lighe bothy, a stone building with a fireplace that the Mountain Bothy Association renovated in 2013 after it was accidentally burnt down), a bluebird winter’s day hiking entirely on our own up a striking peak with a narrow ridgeline (the 909m high Corbett, Streap, which is located right across the glen) and pure and simple hard work (after we descended 650m to the waters of Allt Coire na Streap we had a relentlessly steep 400m ascent back up to the ridgeline to where we are in this photograph). Add in a setting sun, which we just caught before it dipped below the horizon, the fine view we had across to Ben Nevis, the UK’s highest peak, and a descent by head-torch down a steep gully in the dark (lured by the thought of hot food and whisky back in the bothy to finish the day) and it had all the ingredients I like to look for when I’m planning a trip away in Scotland’s hills.

Weekend Wonder - Corrour Bothy

Walking and staying overnight in a mountain bothy in Cairngorms National Park, Scotland.

Published in Adventure Travel magazine as part of regular material I created for their ‘Weekend Wonders’ feature.

Bothies are unlocked shelters dotted about the UK, many of them managed on limited funds by the Mountain Bothies Association (MBA). Often remote, bothies vary in quality and, if you're like me, your feelings towards them can change depending on how tired you are or how bad the weather is outside. (Even a really basic bothy can be a delight when the weather is foul).

Corrour bothy, located in the Cairngorms National Park, is one of the more popular Scottish bothies. It’s not far from my home and I’ve made multiple trips there over the years.

The range of feelings I’ve experienced at Corrour bothy includes;

Enlightenment - through long, varied conversations with like-minded souls I otherwise wouldn’t have met

Happiness - to live in a country where I can freely wander up hills and through glens and stay out overnight

Annoyance - to find lots of garbage left behind by previous parties (there's no rubbish collection service in mountain bothies)

Satisfaction - as I sat outside with a dram on a beautiful Summer's evening after a trek over the Lairig Ghru

Relief - to reach the shelter of the bothy in the midst of a full Winter storm

Overall, my main feeling towards mountain bothies is one of contentment. From knowing that bothies exist and I can stop for a break from the outdoors if I want to, as on this day one Autumn when I walked door to door from the National Trust base camp at Mar Lodge over Devil's Point, Cairn Toul, Sgor an Lochain Uaine and Braeraich, four of the great Munros in Cairngorms National Park, during a fantastic hike that took me over 16 hours.

How to get to Corrour bothy

The Mountain Bothy Association publishes details of bothies on their website (www.mountainbothies.org.uk). You'll find Corrour bothy at GR NN981958 on OS Landranger map 36. It can be accessed from the south-east from Braemar via Glen Lui or from Aviemore in the north via the Lairig Gru.

Other bothies to visit

Less well known bothies worth a visit include Glencoul and Glendhu bothy near Kylesku, the Schoolhouse bothy near the Munro Seana Braigh and the fantastically-positioned Lookout bothy on the northern tip of the Isle of Skye, at Rubha Huinish.

If you do visit bothies, be aware of the bothy code;

Respect other users

Respect the bothy

Respect the surroundings

Respect the agreement with the estate

Respect the restriction on numbers

Viewpoint — Glen Coe summit camp

A feature in Outdoor Photography magazine about a wild camp on the rocky summit of Stob Coire nan Lochan above Glen Coe in Scotland.

Written for and published by UK Outdoor Photography magazine.

Each year, in Summer, I like to take a few weeks out of Scotland’s mountains to let the temperature cool down and remove myself from the scourge that is the Scottish midge. By the time the cooler months of September and October arrive, I’m looking forward to ending my self-imposed exile and heading back into the hills.

My goal for this occasion was to sleep atop a mountain peak, photograph the sunrise for a personal client and scope out a location for a mountain running photo shoot I had pencilled in for later in the year. The internet is such a valuable resource these days for a landscape photographer and there’s many useful tools that will aid your planning (such as Google Maps, Google Images, Fatmap or the Sunseeker or Photographer’s Ephemeris mobile apps). You can research in detail exactly which locations should be worth going to and when, with the huge advantage of knowing in advance where the light will fall. A great deal of work can be done at home or in the office and if you’ve planned correctly, it’s simply a case of waiting and hoping for a spell of good weather.

For this trip, I’d researched an ascent of Stob Coire nan Lochan, a 1115m high rocky summit above Glen Coe in the West Highlands of Scotland, part of the Bidean nam Bian massif. I’d worked in Glen Coe before and relished the idea of heading back. For good reason — the landscape is incredibly varied for such a small place.

Parking is available at the popular Pass of Glen Coe and, in the early evening, I trekked into Coire nan Lochan, enjoying the effort of my ascent as darkness fell. The ground was familiar as I’d been in the corrie before, on route to a popular winter climb called Dorsal Arete. Scrambling up the rocky flanks of Stob Coire nan Lochan by head-torch was interesting and good fun and I was welcomed on the summit by cool, dry air, carried on a slight breeze. Settling in to my warm bivvy, I listened to the sound of stags braying loudly in the glens below and soon fell asleep.

Early morning light

One of the benefits of photographing in Autumn is you don’t need to be up super early to catch the dawn. Sunrise was indicated as 7:37am and I was up at a very pleasant time of 7.00am. As I expected, I was on my own, with an uninterrupted 360-degree view of Scottish glens and mountains. Swinging my arms to warm up (I hadn’t brought a stove, to save weight), I set up my tripod, camera and wireless trigger in the gloomy light of pre-dawn, pre-visualised compositions I felt would be worthy to photograph and waited to see what would happen. Unfortunately, I wasn’t blessed with the most colourful sunrise but I was witness to some wonderful views as clouds formed in the glens beneath me and, as they rose they draped over the peaks, shafts of light piercing through the clouds and lighting up the landscape.

In all, I spent a very special few hours, in beautiful silence, switching between wide angle and telephoto lenses and shooting as many different compositions as I felt were worthwhile, lingering until dawn had truly broken, and the interesting light had gone. I then packed up and climbed to the summit of Bidean nam Bian (one of the 282 ‘Munros’, Scottish peaks over 3,000ft high), continuing along an easy ridge to a second Munro, Stob Coire Sgreamhach, before I retraced my steps to the head of the evocatively titled ‘Lost Valley’, and headed for home.

Viewpoint information

Distances in miles from nearest large town and nearest city

17 miles from Fort William

118 miles from Edinburgh

81 miles from Inverness

Access rating

5 — Mountain summit reached by some rock scrambling

How to get there

Travel the A82 road to reach the obvious main car park in Glen Coe. Depending on the time of day, this car park may be very busy and a bagpiper playing to the crowds — some smaller parking locations are nearby. Climb the path into Coire nan Lochan — one easy scrambling bit — then, when you each a prominent waterfall, head left on scree and scramble on slightly more difficult ground up the east ridge of Stob Coire nan Lochan to the summit. (A map and compass and the skills to use them is essential. Visit a dedicated walking resource, e.g. www.walkhighlands.co.uk, for more detailed instructions).

What to shoot

Wide angles of remote glens and mountain ridges with the A82 road, c.2,500ft beneath your feet. Switch to a telephoto zoom lens and pull out detail in the rocky cliffs beneath the summit of the nearby Munro, Bidean nam Bian (the highest point in Argyll). The infamous Aonach Eagach or ‘notched ridge’ is straight across the glen.

Best time of day

Any time of day for general photographs (expansive 360 degree views from summit). Best at dawn for the sun lighting up the glens and peaks to the east. Bivvying the evening before on Stob Coire nan Lochan is an option but the summit is very rocky and not altogether flat.

Nearest food/drink

Clachaig Inn, Glencoe, Argyll, PH49 4HX

W: www.clachaig.com

E: frontdesk@clachaig.com

T: +44 (0) 1855 811252

Nearest accommodation

Clachaig Inn, Glencoe — www.clachaig.com

Kingshouse Hotel — www.kingshousehotel.co.uk

Other times of year

Winter and Spring light in Glen Coe can be magical but mountaineering knowledge, skills and equipment are required to reach the summits when the ground is covered in snow and ice.

Ordnance Survey

OS Landranger map series 41 — Ben Nevis Fort William & Glen Coe

Nearby photography locations

Buachaille Etive Mor — 1 mile

Loch Etive (Glen Etive) — 17 miles

Lochan na h-Achlais (Rannoch Moor) — 11 miles

Weekend Wonder - Isle of Rum

Exploring the ‘other Cuillin’, on the Isle of Rum in the North-West Highlands of Scotland.

Published in Adventure Travel magazine as part of regular material I created for their ‘Weekend Wonders’ feature.

The Isle of Rum is a National Nature Reserve and a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). There are no roads on the island and reaching it involves a boat trip, adding to the feeling of an adventure. The jewel of the island for walkers and climbers is the Rum Cuillin, which, like their counterpart, the Black Cuillin on the Isle of Skye, offers excellent rock scrambling along narrow ridges to mountain summits jutting above the Sea of the Hebrides, with great views out to the Atlantic Ocean.

Bill Snee descending to Dibidil bothy on the Isle of Rum, Scotland

The highlights of my visits to Rum have been hillwalking and backpacking trips on Ainshval and Askival, two of Rum's Corbetts. Although only c.2,500ft high, the view from both peaks is spectacular - a 360 degree view taking in Skye, Eigg, Muick, Canna, the Hebrides and much of Scotland's mainland west coast. On one occasion, on a sweltering bank holiday weekend in May, we bivvied on Ainshval's summit during an epic 3-day expedition where we climbed all Rum's hills, soaking in the heat and the views as the sun set as a fiery orange ball on the horizon. On another trip, pouring rain caused us to bail on a traverse of the Cuillin ridge into the Atlantic Corrie, a gigantic, amazing amphitheatre filled with seemingly no less giant stags that stood their ground and defiantly roared at us as we interrupted their rutting season.

Fortunately, my ratio of good days on the island outweighs the bad days. This includes the day we descended from Askival (pictured), after a brilliant Summer's day's hillwalking, which culminated in an engaging night making new friends at Dibidil bothy on the shoreline.

Getting there and around

Caledonian MacBrayne (www.calmac.co.uk) and Arisaig Marine (www.arisaig.co.uk) both offer easiest access to the island, via their ferry service. For venturing thereon in, you'll need to don your walking shoes. If heading anywhere remote, take standard hillwalking gear (e.g. warm clothes, waterproofs and gloves) plus be experienced in the use of a map (OS Landranger 39) and a compass.

Places to stay

The 'capital' of Rum, Kinloch, has an organised campsite plus cabins for hire. The Isle of Rum Community Trust operates a bunkhouse. Wild camping is an option all over the island (as long as you follow the Scottish Outdoor Access Code). Alternatively, choose to go basic and stay at one (or both) of the island's two mountain bothies - Dibidil bothy and Guirdil bothy). Read more about your options on the island's great website – www.isleofrum.com.

Weekend Wonder - Lochnagar’s mighty cliffs

An opportunity, perhaps. to see the Royal Family on Lochnagar, a Munro in Cairngorms National Park, Scotland.

Published in Adventure Travel magazine as part of regular material I created for their ‘Weekend Wonders’ feature.

Lochnagar, a 1155m high Munro in the Cairngorms National Park in Scotland, is a mountain with royal connections. The peak, located nearby Balmoral Castle, is the summer home of the Queen and the Queen's first son, Prince Charles, has been known to climb the hill when the family is in residence.

Alex Haken traversing the top of the steep cliffs on Lochnagar in Scotland

I had made two attempts to climb Lochnagar before this image was taken. Both times were in the depths of winter and on neither occasion did I meet another soul on the hill, royal or not. On my first attempt, I didn't get past the bealach beneath Meikle Pap, regularly unable to stand on two feet due to strong winds, and on my return I was thwarted at Cac Carn Mor, a giant cairn on the plateau at 1150m, just 5m shy of summit height but 0.5km away of the true summit, Cac Carn Beag. Not because it is slightly confusing (I believe a Mor is 'bigger' than a Beag so you would be forgiven for thinking it would be the summit) but again because of the weather. Great gusts of wind that had built speed over the surrounding rolling hills swept across the plateau and threatened to launch me off the top of Lochnagar's spectacular cliffs. These cliffs, some 200m high in places, hold lots of summer rock climbs and winter ice climbs. I don't believe they are appropriate for base jumping (even with a parachute) so, after a few calls that were too close for comfort, I half walked half crab-crawled my way back to the relative shelter of the approach path and returned with a friend in more amenable weather.

Getting there and around

Lochnagar is usually climbed as a day trip from the Spittal of Glenmuick. For added spice, head in from the North near Invercauld Bridge on the A93 Ballater to Braemar road and climb the great Stuic Buttress, a grade 1 scramble that takes you out onto the plateau near the summit of Carn ' Choire Bhoideach. From there, it's a simple 2km stroll across the plateau to Lochnagar. Alternatively, to enjoy the peak during an overnight trip, walk along the shores of Loch Muick and camp beneath the great cliffs near the Dubh Loch. You can tick off four Munros as you make your way back across the plateau to Cac Carn Beag and your fifth Munro of the day.